Mladen and Del review: ‘Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb’

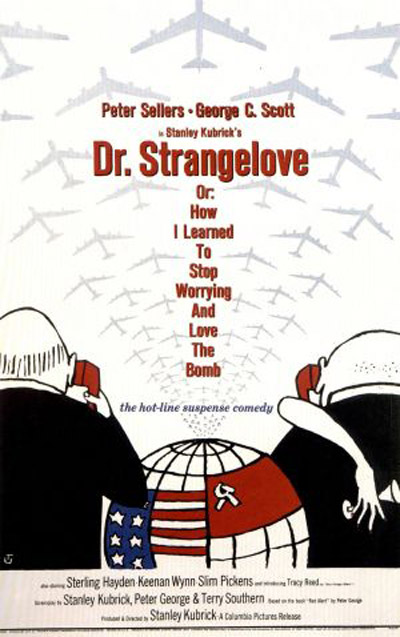

“Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” Starring Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Sterling Hayden, Keenan Wynn, James Earl Jones and Slim Pickens. Directed by Stanley Kubrick. 93 minutes. Rated “approved.”

Mladen’s take

Ever have one of these days?

You can’t find the car keys until you’re already late for work. Then, the starter clicks a couple of times before cranking the engine. Finally on the road, you get a flat tire. While you’re changing the flat, the vehicle slips off the jack and crushes your foot. In the ER, you get a doctor who has prescribed himself a few too many medications and he mucks repairing your foot. An infection comes along while you’re recovering from the faulty service. Antibiotics fail and the only way to contain the infection is by amputating your leg. The intern performing the amputation sneezes during the procedure, severing your femoral artery. You die.

The simile illustrates, roughly, what happens in Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, “Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.”

I watched the 1964 movie a couple of weeks ago. It’s clear that “Dr. Strangelove” is entirely relevant today. In short, Kubrick imagines thermonuclear Armageddon unfolding as a series of seemingly absurd, unlikely events stacking atop each other until the only people left alive are the ones who made the all-destructive atomic war possible.

The idea in “Strangelove” that mistakes, be they failures of thought or products of psychosis would lead to the planet’s fiery, H-bomb-induced demise could have come from today’s headlines. A USAF bomber was flown from North Dakota to Louisiana in August 2007 with six nuclear warhead-tipped cruise missiles hanging from a rack. No one at the wing, including the flight crew, knew the nukes were aboard the bomber until it arrived at Barksdale Air Force Base. A year earlier, American supply troops sent ICBM nose cone fuzes to Taiwan thinking they were helicopter parts.

Attention to details, particularly the movie’s calm demeanor as the B-52 crew receives the order to nuke an adversary and the meticulous, as-a-matter-of-fact way it arms a warhead, left me feeling that war was largely a bureaucratic affair uprooted from consequences. Following procedures, rather than questioning them, drove humanity over the edge in “Strangelove.”

To me, “Strangelove” offers sardonic relief best captured in the military motto – “Peace is our profession” – that frequently appears in the movie. I know nuclear holocaust is on the way. You know nuclear holocaust is on the way. Kubrick and “Strangelove” allow me to laugh at the prospect.

Del‘s take

At the risk of dating myself I remember the Cuban missile crisis, backyard bomb shelters and drills where we kids would be hustled into an interior room at the school to ride out the onslaught of inbound ICBMs.

It was not funny.

But that was life in the early ‘60s and oddly my recollection of those events seems framed in a black-and-white panorama of worry and fear, much like “Dr. Strangelove,” which deploys its dark humor to accentuate the absurdity of mutually assured destruction.

For those of you who missed this cinematic classic, here’s the plot: An Air Force general becomes convinced the communists are subverting America through fluoridated water. He dispatches a wing of nuclear-armed B-52s to destroy the Soviet Union. The Strategic Air Command is made aware of the situation and huddles with the president in the “War Room” to devise a strategy for recalling the bombers. The Russian ambassador is brought in and reveals the existence of a “doomsday device,” a network of cobalt-jacketed hydrogen bombs that will spread lethal radiation across the world if Russia is nuked. The bombers are recalled, but one, damaged by an anti-aircraft missile, continues on its mission. …

“Strangelove” provides a canvas for stunning performances by George C. Scott, Sterling Hayden, Keenan Wynn, Slim Pickens and most notably Peter Sellers of “Pink Panther” fame, who plays three roles, that of R.A.F. Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, President Merkin Muffley and Dr. Strangelove himself, a wheelchair-bound Nazi scientist who wages a minute-by-minute battle with his black-gloved hand for control of his loyalties – to his new American friends or his old friends at the Reichstag.

But “Strangelove’s” best performance comes from the screenplay, written by director Stanley Kubrick, which skewers all the institutions Americans relied on to guide them through the Cold War: the military, the government, and what most people would call common sense. As the B-52s streak toward the Soviet Union, Scott’s Gen. Buck Turgidson argues for an all-out attack – and why not? “We could catch them with their pants down!” Turgidson enthuses.

“Strangelove” is so steeped in historical context that nobody under the age 45 is likely to grasp its sophistication and nuance – a skill of perception sadly lacking in contemporary audiences. Yet “Strangelove” is one of the 20th century’s greatest films, serving up a damning indictment of bureaucracy, the military-industrial complex and a simple-minded us-or-them worldview that cannot exist in today’s interconnected global village.

“Gentlemen!” President Muffley shouts as Turgidson and Russian ambassador Alexi de Sadesky grapple over a secret camera. “You can’t fight in here! This is the War Room!”

As John McCain might say, “That, my friends, is ‘Dr. Strangelove. ’ ”

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical editor. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

Video