Del and Mladen review ‘The Arbors’

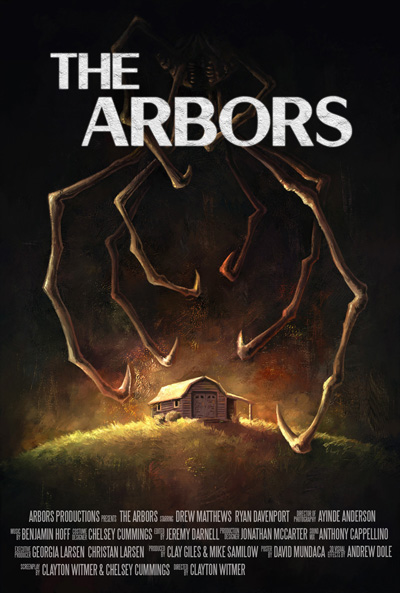

Image courtesy of The Arbors Production with The Red Arrow Studios Company.

“The Arbors” Starring Drew Matthews, Ryan Davenport, Sarah Cochrane and Alexandra Rose. Directed by Clayton Witmer. 1 hour, 59 minutes. Unrated. Streaming on Amazon Prime, Tubi TV.

Del’s take

Ethan Duanes (Drew Matthews) has a problem.

His problem is life.

Ethan is a locksmith but he cannot unlock the secret to happiness. All he can do is remember an earlier time when his parents were still alive and his younger brother a constant companion. The world seemed better then.

Now, the world isn’t better. His parents have passed away and his brother, Shane (Ryan Davenport), has started a family. The ancestral home, like Ethan, is slowly succumbing to rot and ruin, and the future seems as dark as the night shifts Ethan works.

One night, as Ethan is driving back to his rented house after a call, he comes across a dead deer in the road. He notices something moving inside the deer, a kind of insect or arachnid. He takes the carcass home, builds a container to hold the strange creature and lures it inside with cuts of meat. Then, he proceeds to care for it.

Until the creature breaks out. And people in the community begin to die.

That is the premise of “The Arbors,” a “monster movie” that isn’t a “monster movie.” It is less about things that go bump in the night as things that go bump in the heart.

“The Arbors” earns high marks for its layers and its obvious pathos. Ethan is a sympathetic loser to whom many people can relate: He is overwhelmed by life, fearful of change and nostalgic for the simpler times of the past. This theme of resistance to change operates throughout the movie – Ethan says it more than once by rhetorically asking, “Can’t this all be over?” His fidelity to the past is expressed in other ways, too. He is constantly sorting through photographs of him and his brother when they were kids. He gives his brother the gift of a toy soldier from a game they played as children called Out of Time! Ethan has kept the game; his brother absent-mindedly drops the toy soldier on the floor and before movie’s end it returns to Ethan’s possession. Ethan tells his young niece, Robin (Sarah Cochrane), he hopes to purchase the family home and restore it so that he may live there again. When Shane reveals he and his wife, Lynn (Alexandra Rose) are contemplating a move out of state, Ethan becomes agitated and for once, shows strong emotion.

Where “The Arbors” fails is its glacial pacing and the infuriating passivity of its viewpoint character. Ethan doesn’t simply miss the past; he is mired in it and will never escape. He rejects chance after chance to change his circumstances, at one point avoiding a former friend who has offered to take him away from his ennui and show him the world. In truth he doesn’t want to escape, and he would draw everybody around him into the tar pit of his inertia. This slow vortex of apathy oozes over both character and audience alike, preserving the misery in a sluggish and vapid shadowbox that never answers the question “Why?”

And when the “monster” kills people who have threatened Ethan’s attempt to restore the past to the present, “The Arbors” morphs into “Donnie Darko” and the audience is left with a new batch of questions.

What’s remarkable about “The Arbors” is that it was shot in the Winston-Salem, N.C., area in 25 days on a budget of $14,000, then finished for another $11,000.

Witmer deserves kudos for trying to rise above the meager expectations of the genre, but “The Arbors” has some deficiencies that outweigh its virtues. Still, it’s not a bad movie. Just slow, with unanswered questions and motivations. I expect Witmer will do better his next time out of the gate.

I grade “The Arbors” a C+.

Mladen’s take

Through much of “The Arbors” I kept telling myself, “Wow, the kid playing the principal misfit really looks like a young Dennis Quaid.”

That’s how I managed to stay entertained when “The Arbors” got batty or the story cryptic or incoherent, which wasn’t all the time. Just much of the time.

Del blew a lot of words summing the plot. I’ll do it for you with one, short sentence: Rogue nostalgia is a deadly when you’re connected to person-sized spider with a mammal-like mouth packing white shark teeth.

One of my biggest problems with the movie is that I have no idea how or why Ethan and pseudo-spider are telepathically linked. If I was the angry wayward mutant arachnid, I’d be pissed at Ethan for putting me in a cage when I was but a maggot or whatever. That would be reason enough to eat his eyeballs rather than serve as an executioner for the human.

And, who the hell where those guys in the white hazmat suits? And, why didn’t at least one of them have a gun for self-defense because they were chasing an aberration of nature?

I don’t mind that “The Arbors” portrays itself as horror but is really about shitty, navel-gazing stuff like hurt feelings. People, after all, are more frightening than zombie werewolves with rabies waving Trump is My President flags. But, at times, I felt like I was watching, I don’t know, “Kramer v. Kramer” or “Steel Magnolias.”

The problem is that the film seems to want to get good and then backs off. A scene of driving at night might be too long. Or there’s the crappy voice acting when Ethan is talking to someone on his flip phone. Yes, director, I get it that Ethan is stuck in a time that no longer exists. And, why the fuck does “Connie” care about Ethan? She didn’t even sign his high school yearbook. What proof is there that she let him feel her up when they were teenagers or that they went to prom together? She materializes, tries to get him to leave town, and then de-materializes.

On the plus side, “The Arbors” provides a holistic moodiness as the backdrop of life in an unnamed town somewhere in the foothills of the Appalachians. Everything seems afflicted by Ethan’s desperate unhappiness. I liked the score. It meshed nicely with the moodiness.

The movie gets a C- because it failed to meet its promise to me like life failed to meet its promise to Ethan. It didn’t allow him to stay 13 years old forever. And, the film failed to create a sympathetic, lonely man with control of a monster who I could like.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

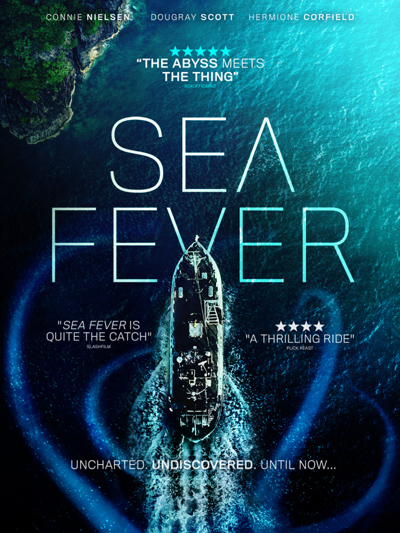

Image courtesy of Signature Entertainment.

“Sea Fever” Starring Hermoine Corfield, Dag Malmberg, Jack Hickey, Dougray Scott and others. Directed by Neasa Hardiman. 95 minutes. Unrated. Hulu, Vudu, Google Play, Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, YouTube.

Del’s take

Oh goodie. Let’s distract ourselves from the pandemic by watching a movie about a pandemic.

Not a pandemic per se but a parasitic infection that threatens to wipe out the crew of an Irish fishing trawler plying the chilly waters of the North Atlantic. That’s the gist of “Sea Fever,” a pretty good little monster movie from director Neasa Hardiman. If films speak to the times, “Sea Fever” is the voice of our COVID-19 consciousness, transposing our empty streets and restaurants with the vacant horizon of the open ocean.

The plot is familiar to fans of “Alien,” “The Thing” and even “The Shining.” Lonely, friendless PhD student Siobhán (Hermoine Corfield) has booked passage on the Niamh Cinn Óir, a rust bucket Irish fishing trawler, to study the behavior patterns of aquatic fauna. The Niamh Cinn Óir is owned and operated by the husband-and-wife team of Gerard (Dougray Scott) and Freya (Connie Nielson); and a crew of four others. Life has not been grand for Gerard and Freya, and they need a good haul this trip or they’ll lose the trawler.

On the trip out they detect a large mass of fish which unfortunately lies within a government-declared exclusion zone. It would be a terrible thing if they accidentally drifted into that exclusion zone and caught a hold full of mackerel, thus saving the Niamh Cinn Óir from receivership and preserving the crew’s livelihoods. Well gosh darn it, guess what happens.

Sometimes exclusion zones exist for more reasons than bureaucratic capriciousness, especially in movies that isolate a small group of people and pits them against a seemingly unbeatable antagonist. It is at this point “Sea Fever” becomes a metaphor for the COVID-19 pandemic as the fishing trawler crew battles a weird aquatic parasite that threatens to kill them all.

But “Sea Fever” operates on a second level, one that addresses the pandemic of loneliness that has infected the world since the invention of digital technology. On her first field study, Siobhán is forced to step out of her reclusive shell and interact, if not befriend, the crew, especially after they discover she’s a redhead (apparently redheads are considered bad luck among Irish fishermen). As the movie progresses along its somewhat predictable trajectory, Siobhán becomes more and more human as her environment descends into science fiction nightmare.

Somehow indie directors always manage to find strong actors to fill their roles and “Sea Fever” is no exception. All the performances are very good but my favorite was Olwen Fouéré as Ciara, the boat’s cook, who carried herself with a chafing blue collar dignity that seemed to perfectly capture the soul of the part. Another strong performance was delivered by Ardalan Esmaili as the boat’s principled and skillful engineer. Weakest was Dougray Scott, whose character hovered somewhere between effective leader and simpering cad. He seemed incapable of communicating the moral ambivalence of a man caught between financial necessity and obeyance of the law.

My gripes with “Sea Fever” are that it wraps up with an anticlimax that feels rushed and out of character for protagonist Siobhán, and the crew’s attempts to resolve their problem seem truncated and drama-less. What would Ellen Ripley have done had she been aboard the Niamh Cinn Óir? That might have elevated the tension considerably.

Still, “Sea Fever” is, as I said, a pretty good little monster movie and your time will not have been wasted, if monster movies are your bag. As American movies become more and more templated by the MBAs working in Hollywood these days, it’s nice to see a movie that still has character and a beating heart.

I grade “Sea Fever” a B or maybe even a B+.

Mladen’s take

Desperation. Superstition. Science. And, a cnidarian. Say it with me, “cnidarian.” I adore that word. It wasn’t in my plain old lexicon of the English language. I had to look it up in my Oxford Dictionary of Science. Cnidarian. Cnidaria is a phylum of aquatic invertebrates that includes hydra, jellyfish, sea anemones, and coral, by the way.

In “Sea Fever,” the crew of the fishing vessel Niamh Cinn Óir become the victims of a cnidarian unknown to humanity. First, the oversized spineless predator whose centrally placed orifice is both mouth and anus, attacks their boat and then it attacks them with its eye-eating larvae.

Where Del sees a SARS-COV-2 angle to “Sea Fever,” I see a straight-up Nature will always kick Man’s ass statement in the film. Humanity believes it controls the planet. The planet disagrees. That disagreement takes many shapes. Climate change. Water shortages. Invasive species. A snowstorm in Texas that has Tumbleweed Cruz abandoning the state he represents in the U.S. Senate to flee to warm and socialist Mexico.

Though the encounter with the cnidarian drives the plot of “Sea Fever,” the story is also about society-induced desperation. The boat owner, who’s married to the captain, has to land a good catch to earn euros to keep the vessel. With that thought plaguing the couple, the captain takes a risk and then the boat owner takes a risk. Both prove fateful.

There is superstition aboard Niamh Cinn Óir. Marine biologist Siobhán, on the boat to conduct field research that her PhD advisor ordered her to do, has red hair, which, as Del points out, the crew consider bad luck. But, there’s also the superstition of religion. There is prayer for a safe journey. There is prayer for a good haul of fish. There are prayers for the dearly departed. And there’s the belief that God will yet protect the crew.

There is science aboard the boat. Siobhán, applying her knowledge, figures out enough about the big cnidarian to give the crew somewhat of a fighting chance to live.

But, in the end, neither God nor science are much help. What mattered was one person sacrificing for another.

“Sea Fever,” as Del claims, is a pretty good little monster movie. I would amend that observation with, “pretty good little sci-fi monster movie.” Though not laden with science, the movie has moments of science-y jargon – “cnidarian” for example – and “bioluminescence” and “holopalegic” and a portable, computer-powered microscope, and talk of water filtration system design. There was the hypothesis that the cnidarian normally parasitizes whales (the fishing boat was in an exclusion zone that existed to protect cetaceans and their calves) and might have mistook the passing shadow of the vessel as a sign of its normal prey.

Between trying to stay alive while a gelatinous, tentacled predator treats them as a larder for its babies and keeping themselves from going berserk under the pressure of looming infection, the crew has to struggle with a bigger question. Is it ethical to return to port when some, if not all, of the crew are nurseries for a novel parasite that could, or is it would, infect landlubbers? Poof, see you later, humanity.

The problem with “Sea Fever” is that it added baggage that didn’t need to be in the film. Too much time was used to set up Siobhán as a loner and it was unconvincing. Del mentioned that the cook carried herself “with a chafing blue collar dignity.” Chafing she was, but it was me who got chafed. The cook went from a semi-pleasant grandmotherly type to an old crone who wanted to kill my beloved Siobhán. What would be the point of killing the one person who had the technical know-how to help people stay alive?

Regrettably, I find myself in the unforgivable situation of agreeing with Del. “Sea Fever” is a B. But for a couple of tweaks, including more encounters with momma cnidarian, this movie would have easily catapulted to an A.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

Image courtesy of Warner Brothers.

“Godzilla” Starring Aaron Taylor Johnson, Elizabeth Olsen, Brian Cranston. Directed by Gareth Edwards. 123 minutes. Rated PG-13.

Mladen’s take:

The obvious first. The new Godzilla film stinks. Don’t let Del’s opinion fool you. He doesn’t know Godzilla from Godthab … the capital of Greenland.

Discussing the movie’s plot and acting is pointless because its star is nothing more than Godzilla-like. For example, I’m Brad Pitt-like because I’m an upright walking biped.

So, let’s talk monster morphology and physiology from a purist’s perspective.

I’ll use Toho Studio’s last major Godzilla type, the one that debuted in the film “Godzilla 2000.” It’s labeled AG for “Authentic Godzilla.” The Godzilla-like animal in the new film is “Poser.”

Godzilla from afar.

• AG: An upright walking monster with distinct body parts, such as a neck, prominent spine plates mimicking curved blades, and contoured limbs. The tail is longer than AG is tall.

• Poser: A hunched garden slug-like silhouette with a small head attached to an anorexic body that terminates in legs with, get this, cankles. Its back plates are stunted and the tail short, almost stubby.

Godzilla up close.

• AG: Sleek, cat-like head large, expressive eyes looking forward and a mouth featuring large, expressive canines.

• Poser: Small head with nearly colorless beads for eyes tucked into a puffy face, as though the animal was dehydrated from an all-night drinking party. Put together, the face is a blur with its major components – snout, forehead, and jaw – blending into each other almost indistinguishably.

Godzilla’s fire breath.

• AG: A searing plasma, white-amber in color and liquid in texture, projected from the monster’s mouth. It’s launched with a head movement. AG’s head rotates sideways 30, 40 degrees and then juts forward. The monster sometimes takes a step toward its target, maybe to brace against the death ray’s recoil. When the fire breath hits, it explodes, engulfing the target. It is preceded by the spine plates glowing the same vivid color. They heat the air around them, causing convection currents.

• Poser: A feeble blue that looks like its origin is a LED light someone stuck into Poser’s throat. Come on, the death ray is supposed to be generated by nuclear fission, not your local electric company. The spines glow the same soothing blue. There’s nothing intimidating about Poser’s fire breath attack and it barely damages the critter it’s fighting.

A caveat before I address Godzilla’s signature physiological trait, the one that stays the same no matter the monster’s Toho iterations. It could have rescued the new Godzilla film, though the creature’s morphology was sullied.

I appreciate the director taking Godzilla seriously. The monster isn’t mocked as it was in the other Hollywood re-make of Godzilla starring Matthew Broderick. And, there a couple of deferential nods to the Godzilla franchise’s early years.

That three, let alone one, giant monster, can exist today is treated plausibly and sincerely. The acting wasn’t bad and the plot good.

It’s just tough for me to accept that there’s not enough imagination out there in moviemaking land despite the graphics computing power available to modern-day producers and directors to render a classic Godzilla as a force of nature by making it look, well, natural and fearsome and indestructible.

Okay, now the one indelible physiological must for all Godzillas: its roar-screech.

• AG: A growling rumble rapidly ascending in pitch to a banshee wail that then trails off. I don’t know, it’s the sound of a titanium spike scraping across a steel ingot with the frequency slowed and amplified. Or, the roar-screech mimics an elephant’s trumpet inside an echo chamber that amplifies lower tones, while distorting all of the sound.

• Poser: A grizzly bear with laryngitis.

I give the new Godzilla an A for effort and C+ for execution.

And, I’m still trying to figure out why Godzilla faints near the end of the movie. Was it tired from its battle against the other monsters, which resembled a cross between the Gyaos in Gamera movies and the alien invader in “Cloverfield.”

Or, was the director trying to build sympathy for the monster by making it look like it had died to save mankind?

If it was the latter, the director failed because he never developed Godzilla’s personality and, believe me when I say, Godzilla in past renditions had a lot of it.

Del’s take:

I broke Mladen’s heart because I wouldn’t come to his house and listen to a proper Godzilla roar in Dolby SurroundSound.

Sorry, Mladen. Godzilla’s roar, or whether he was fat, or if his head was too small, weren’t on my list of priorities.

What I wanted from “Godzilla” is what I want from every movie – interesting characters who generate empathy, a decent plot, dialogue that works, and a set of rules consistent with the movie’s internal logic.

What I got was boring characters about whom I cared little, a bullet-riddled plot, flat-affect dialogue, and a set of rules that were indeed consistent with the movie’s absurd internal logic.

“Godzilla” opens with a cool segment of backstory: The Pacific nuclear “tests” of the 1940s and ’50s were attempts to kill the giant serpent. The movie then segues to a Fukishima-style disaster at a nuclear facility in Japan. Brian Cranston’s character is the director of the facility, and during the disaster his wife dies in a reactor breach. Jump to today – Cranston’s son, played by Aaron Taylor Johnson, is an explosive ordnance disposal technician who flies to Japan to bail his father out of jail. Seems daddy believes Japanese authorities are hiding something at the reactor disaster site and he’s right – a giant monster has been feeding on the radiation and springs into the world – make that “stomps” – just as Cranston and son arrive at the site.

What follows is a jaunt halfway across the world as the monster makes its way to Yucca Mountain, America’s nuclear waste disposal site (which, by the way, contains no nuclear waste, as its commission was halted by the Obama administration) to meet up with a second MUTO (massive unidentified terrestrial organism) and hatch a batch of monster babies (totally overlooking the two Diablo Canyon nuclear facilities between Los Angeles and San Francisco).

Luckily for mankind, Godzilla is in pursuit as its place as the top alpha predator is threatened by the MUTOs (which bear more than a family resemblance to the monster in “Cloverfield”).

Cranston is able to imbue his role with emotion, but Johnson and Olsen spend most of the film gazing dumbly into the distance. They simply have nothing to say, and it was impossible for me to develop any affection for either. A Japanese scientist, played by Ken Watanabe, is kept by the military as an adviser, but spends most of his time mouthing gassy admonitions about the perils of pissing off Mother Nature.

The characters are wasted.

Special effects are superb, though I grew tired of the gray and brown color palette. The score is at times shrieky, helping the action on the screen to lapse into farce. Edwards’ directorial style is interesting, though I’d say he relied to heavily on foreshadowing. After we’ve seen the monsters, there’s no point in showing us the aftermath of their rampages. Let’s see the buildings tumble!

To me, Godzilla is a metaphor for whatever issue rules the day – nuclear warfare, man tampering with nature, you name it.

But in “Godzilla,” the monster strikes me as a metaphor for the inability of modern storytellers to tell a decent tale.

Overall, I’d rate it a C+.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical editor. Del Stone Jr. is a journalist and author.

Image courtesy of Universal Pictures.

—

“The Thing” Starring Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Joel Edgerton and Ulrich Thomsen. Directed by Matthijs van Heijningen Jr. 103 minutes. Rated R.

Mladen’s take

Let’s call Director John Carpenter’s 1982 film “The Thing, A.” Let’s call Director Matthijs Van Heijningen’s released-on-Friday movie “The Thing, B.” I do that for two reasons. Those are the grades each movie deserves – actually it’s A+ and B+, respectively. And, it’ll be easier to keep track of which movie I’m referring to because comparisons are inevitable. “The Thing, B” is the prequel to “The Thing, A.”

The “Thing, A” in one of the two finest sci-fi horror movies made. The other is “Alien.”

The formula for success is retained in “The Thing, B.” An isolated group of humans, in this case a multinational research team in the Antarctic. A creature that mercilessly and vividly parasitizes bodies. And, suspense.

My pal Del will probably disagree with the last attribute. Always grumpy and a quibbler, he’d exchange “suspense” for “cheap-shot fear” because there are at least three jump-out-of-your seat moments in “The Thing, B.”

To a degree, I agree with Del.

In the superb “The Thing, A,” the body-snatching, body-cloning alien is portrayed as an amorphous, almost cautious being. It’d prefer to nail you when you’re handy and lashes out only when pursued. That makes the creature scarier because it’s clearly thinking.

In the “The Thing, B,” the alien has a shape of its own. In its original state, the technologically sophisticated arthropod looks like an overgrown wood louse. And, rather than being an ambush predator, like say a praying mantis, it’s an aggressive stalker of anything that moves, like say former U.S. vice president Dick Cheney. That makes the creature more of a monstrosity.

There are implausible moments in the “The Thing, B.” The lead Norwegian scientist ignores American paleontologist Kate Lloyd, portrayed very effectively by Mary Elizabeth Winstead, when she urges that carefully controlled laboratory techniques, including isolation, be used to un-entomb the alien from the ice in which it’s frozen.

Also, the soundtrack used to frame “The Thing, B” is very weak. A day after seeing the film, I’m unable to recall its rhythm or tempo. This is in stark contrast to Ennio Morricone’s foreboding, subtly pulsing, and ingenious score in “The Thing, A.” Sometimes, simple is better. Much, much better.

But, let’s not quibble.

“The Thing, B” takes advantage of the unique elements at its disposal.

Computer-generated graphics are very good and used to enhance the plot, not substitute for it.

Van Heijningen imagines very nicely what would likely happen to a small group of humans confronted by a terrifying fact: If it walks like a human, if it talks like a human, if it behaves like a human, it might not be a human. The scientists act rationally and irrationally as each tries to avoid becoming food for the alien’s DNA. Most notably, as the situation at the Antarctic research outpost deteriorates, the Norwegians and Americans periodically rely on nationality as a source of trust to form us-against-them alliances, though the Thing is uninterested in which flag would hang above its next human victim’s grave. Assuming, of course, there’s anything of the victim’s own remains to recover.

There’s another reason to see “The Thing, B” while it’s in theaters.

Van Heijningen pays tribute, maybe it’s more like deference, to Carpenter’s “The Thing.”

To appreciate the gesture, make sure you’ve seen Carpenter’s film before seeing Heijningen’s and stick around for the credits. Many in the audience started to leave, only to stop, while standing, to watch the end of “The Thing, B.”

Del’s take

Despite Mladen’s warning that I “expect to be disappointed,” I sat down to watch “The Thing” with a degree of hope and not a few questions:

Billed as a prequel to John Carpenter’s 1982 horror-science fiction classic of the same name, would 2011’s “The Thing” merely replicate its masterful predecessor or bring something new to the story?

Would it scare me intellectually or, like so many “scary” films today, employ a CGI festival of fake gore and monsters jumping out of closets to generate cheap thrills?

How successfully would director Heijningen marry this film to – again – Carpenter’s 1982 horror-science fiction classic? (And I emphasize that Carpenter’s film is a classic despite the scorn of critics and moviegoers of the Reagan era. “The Thing” is a testament to tension done right. Heijningen stands much to lose by treading on such ground, as did the creators of the Keannu Reeves sapfest “The Day the Earth Stood Still”).

First, a word about “The Thing’s” lineage. In 1938 author-editor John W. Campbell wrote a novella for a pulp magazine, Astounding Stories, called “Who Goes There?” about a group of Antarctic explorers who discover a crashed UFO and its pilot frozen into the ice. They accidentally destroy the ship but recover the pilot’s body which, upon thawing, reanimates and begins assimilating the crew, mimicking their appearances and manners. What ensues is the familiar, creepy tale of a small group of human beings struggling for survival against a faceless foe, a story that resonates well with today’s terrorism-infused culture in which the enemy walks among us, unseen.

In 1951 “Who Goes There?” became a movie, “The Thing from Another World,” directed by Christian Nyby (although many consider Howard Hawks the real director). It was loosely based on Campbell’s story but deviated in significant and disappointing ways. In 1982 Carpenter’s iteration more closely followed the plot laid down by Campbell and featured nausea-inducing special effects and a depressing storyline that torpedoed the movie at the box office. Fortunately the movie survived in video, then digital form, to become a cult favorite and, dare I say, a mainstream draw for audiences inured to gory nihilism in moviemaking. Both movies effectively conveyed a building sense of dread that pitted an isolated group of humanity against an invisible enemy – in 1951 it was communism; in 1982 it was ourselves.

Along comes Heijningen’s prequel, which takes up a few days before Carpenter’s movie began. Kate Lloyd is an American anthropologist brought to Antarctica by Dr. Sander Halvorson (Thomsen) to examine a mysterious structure and “specimen” the Norwegians have discovered under the ice. When the specimen is recovered and an ill-advised tissue sample taken, shape-shifting hell breaks loose as the thing goes after the camp crew with the ultimate goal of reaching the larger world, where it can infect everybody.

I have a number of gripes with this “Thing,” some small, some not. The small stuff first:

Score: Marco Beltrami’s score is at best forgettable, at worst an opportunity lost. It conveys little of the tension so effectively embodied by Ennio Morricone’s score for the Carpenter film.

Continuity: As a period piece “The Thing” looks pretty much like a 1982 movie. Computer monitors are correctly hulking and snippets of popular music, from bands like Men at Work, reflect the flavor of the times. But then you have lines of dialogue from, let’s say, a character who’s been told to go and get something and answers, “I’m on it.” That expression wasn’t used in 1982 and I know this because I was around in 1982.

Who’s in charge? In Carpenter’s “The Thing” we knew from the first scene that Kurt Russell was in charge. Even when he wasn’t in charge, he was in charge. In this version Winstead oscillates between leadership and submission. You might think that’s an understandable consequence of a woman being immersed in a 1982-era all-male community, but that’s not what I’m talking about. Authority springs from viewpoint, and authority is not effectively conveyed through Winstead’s character. Sigourney Weaver has proved what an effective female lead can do within an all-male community.

My larger gripes include this iteration’s duplication of the Carpenter movie. At times I thought it was the Carpenter movie. Several scenes seem lifted directly from the earlier film, and the overall structure of “The Thing” copies what Carpenter did in 1982 – with some unfortunate exceptions:

While Carpenter filled his movie with quirky, quixotic characters – almost all of whom were dysfunctionally sympathetic – Heijningen’s prequel features only one person I actually cared about, a lethal deficiency for a horror movie. None of the characters stands out as an individual with a unique personality; they’re all just cardboard cut-outs filling roles as they scream their way down the alien’s gullet.

Worse, this version of “The Thing” does not emulate the brooding, palpable dread Carpenter built into his 1982 film. We are quickly thrown into the fray and forgettable people start dying, stalked by a malevolent force, yet another deviation from Carpenter’s classic. In that film you could almost feel a whiff of sympathy for the creature – it was, after all, a hapless castaway thrust into a hostile environment and was trying to survive the only way it knew how. But now we have a stalking predator that, if it wants to escape to the larger world and propagate, thwarts its own intentions time and again.

On a positive note Heijningen brings his movie to a perfect conclusion, matching it directly to Carpenter’s film. This takes place as the end credits roll so be sure not to leave the theater. It’s actually very cool.

Still, the 2011 “The Thing” has assimilated its earlier classic and produced an inferior copy. On a scale of 1 to 10 I would rate it a 5.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical editor. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.