Mladen and Del review ‘Nomadland’

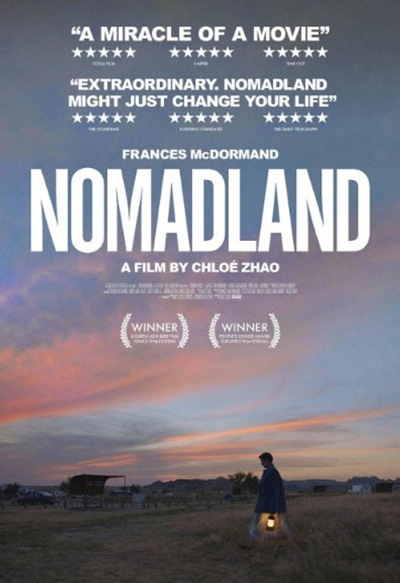

Image courtesy of Searchlight Pictures.

“Nomadland” Starring Frances McDormand, David Strathairn, Linda May, and others. Directed by Chloé Zhao. 107 minutes. Rated R. Hulu.

Mladen’s take

Goddamn, Del, you must hate me. What were you thinking when you suggested we review “Nomadland”? Was it something like, “This will force Mladen to commit suicide, for sure.”

While watching this film, I dropped into a weariness shrouded by miasma as potent as the story told by “Nomadland.” The movie, which carries with it the feel of a documentary, is poignant, spare, ghostly, and perfectly bleak.

To uplift myself, I had no choice but to watch “Judge Dredd” the same night. “Dredd,” the one with Karl Urban as judge, jury, and executioner, made a narcotics-doused, hyperviolent, and environmentally devasted country of the future run by fascist Republicans seem like paradise compared to the U.S. of today portrayed in “Nomadland.”

The principal character in “Nomadland,” Fern, portrayed brilliantly by one of the finest actors in the business, Frances McDormand, is somehow unfathomably sympathetic and gallingly annoying at the same time. Yes, Fern was a grieving widow. Yes, Fern was an older worker displaced by the Great Recession, which destroyed her town when its largest employer, a mining company, shut down. Yes, working as a seasonal employee at an Amazon warehouse is the equivalent of getting exposed to a vast, barren, dehumanizing nothing of a space symbolizing senseless consumerism in which destitute Fern was unable to partake.

What troubled me was Fern’s inability, maybe it was actually an unwillingness, to make a better life for herself. Why did Fern refuse Dave’s kind offer? Portrayed wonderfully by David Strathairn, Dave was a patient, gentle man who did overcome his nomadic ways and, apparently, a troubled past to accept the new and good role that life extended to him, doting grandfather.

I understand the happiness Fern once possessed was destroyed by a depthless sorrow and sense of loss precipitated by unexpected and uncontrollable change to the trajectory of her social life. It’s how I felt every time I read just a snippet about the 2021 CPAC convention.

But, holy shit, “Nomadland” is exquisite, full-throttle hopelessness wrapped in a beautiful, melancholy score and the stark scenery of America’s central plains and its west.

I will never watch this movie again because it frightens me like no other film I’ve seen. I fear “Nomadland” projects what’s heading toward America without using the hyperbole of partisan politics, the ills of rogue science, or the spectacle of wanton violence. The film offers nothing that distracts me from its message. I was unable to dismiss “Nomadland” by saying, “Oh, this isn’t real. It’s just a movie.” Underemployment. Neglect of people who are aging. Dependence on a global economy that plods without direction or mercy. “Nomadland” shows me a world where escaping outdoors to regain balance and shed the desperation of an internet-based society is no longer possible because mankind’s foul imprint is, literally, everywhere you turn. Most of us are on the way to becoming involuntary nomads.

I was troubled, possibly even hated, every minute of “Nomadland.” But, fuck, it’s impossible to give this ghastly peek into the subdued annihilation of a soul anything but an A.

Del’s take

Sorry for the downer, Mladen. My usual remedy for downers is “Reservoir Dogs.”

After my initial viewing of “Nomadland” I wrote that it was one of the “saddest, most depressing” movies I had ever seen, a comment that elicited a fair amount of grief from friends who pointed out the movie’s many virtues.

Describing “Nomadland” as sad and depressing doesn’t mean it isn’t an excellent film, or worthy commentary about the vapid nature of American culture.

Artistically, “Nomadland” is a masterpiece of acting, direction and screenplay. Zhao’s use of the intellectual, cultural and physical desert of America’s West buttresses the movie’s thematic imperatives while providing the necessary infrastructure for telling a story.

On its surface, the film is a study of dissolution. Fern has lost her job, house and husband in short order, so she packs her life into storage and hits the road in a broken down van, drifting from one temporary job to the next, partaking of one temporary relationship to the next. She freezes at night, craps in a bucket and subsists on a diet of fast food, handouts and barter.

At one point she takes a pass on a rare chance at late-in-life love, and at another she revisits the wreckage of her previous life – only to drift away into the sunset. Friends die and become rocks tossed into a campfire as the next minimum-wage job beckons. As Fern embraces this itinerate lifestyle she becomes as hardened and austere as the landscape she inhabits.

But “Nomadland” is more than the story of a woman’s loss of self. As Mladen, in one of his rare moments of lucidity, correctly pointed out, Fern is a symbol for the American dream. Under assault by an evil troika of malignant influences – self-interested corporations that treat people as commodities, incompetent and dishonest political “leaders” who serve themselves, and digital media giants that have distorted any possibility of ever knowing the truth – we get to watch that dream shrivel and die, not in a sudden and merciful blaze of combustion but in Robert Frost’s “slow, smokeless burning of decay.”

For some, “Nomadland” represents a celebration of the so-called freedom offered by a life on the road. Chucking the obligations of job and rut to discover what’s over the next hill is a fantasy as old as America itself and in fact, several of that movement’s real-life advocates appear in the film to hawk their nomadic lifestyle.

But let’s face it, the freedom offered by life on the road is merely an illusion. In “Nomadland” Fern is only as free as her limitations allow. When her van breaks down she’s forced to rely on the charity of a family member, one who is grounded in the reality Fern has repudiated.

A person’s interpretation of a movie is sometimes informed by their place in life, and a good place affords a certain charity of pathos that might allow them to see “Nomadland” as a declaration of “freedom.” Heck, maybe it is.

Or, maybe it isn’t. What I saw was the death of the middle class, and a woman trying to come to terms with her new poverty. They may have called it “freedom,” but it sure looked like the quiet desperation of somebody who knows how this is going to end and can’t do a thing to stop it.

“Nomadland” is an excellent film. But it is also a sad and depressing film, because it’s about what’s happening in America today, and that, my friends, is sad and depressing.

I give it an A.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.