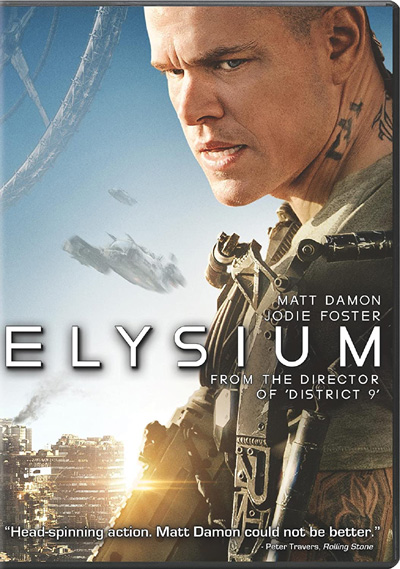

Mladen and Del review ‘Elysium’

Image courtesy of Sony Pictures.

—

“Elysium” Starring Matt Damon, Alice Braga, Jodie Foster and Sharlto Copley. Directed by Neill Blomkamp. 1 hour, 49 minutes. Rated R.

Mladen’s take

It’s tough to criticize a movie where the poor and luckless prevail, because that’s the way the sentimental slugfest “Elysium” ends.

Elysium, derived from the Greek phrase for ideal happiness, is a space station orbiting squalid Earth. The planet in 2154 is a vast slum teeming with poverty, crime and illness. Elysium is a skyborne paradise for wealthies and their “med bays.”

Medical treatment is at the core of this film by the director of nearly perfect “District 9,” which was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar a few years ago. The med bays are scanners that detect bodily maladies and then heal them.

And it’s a med bay that our not always heroic hero Max, played by Matt Damon, has to reach. He can’t buy access to the off-planet treatment, so he becomes part of a grand scheme.

Max, a reformed car thief, has been exposed to a lethal dose of radiation at an Earth-located police android factor where he works. A med bay is the only way to repair his cells. From internally fried body to death is only five days, the extraction droid that pulled Max from the spot he was nuked tells him.

“Elysium” is a movie that requires that you pay attention because there are at least three subplots. The film also asks that you accept at least one far-fetched coincidence.

There’s a villainess, Elysium’s defense secretary Delacourt, played by Jodie Foster.

There’s her Earth-planted, off-the-books paramilitary spook and sadist Kruger, who develops an ambition of his own.

And there’s the other reason Max has to reach Elysium, the daughter of a not-quite love interest, Frey, portrayed by Alice Braga. Frey’s daughter, actress Emma Tremblay, has leukemia and needs access to a med bay, too.

Add a computer hacktivist, machine-to-brain data storage, exoskeletons fused to bodies, solid cussing and graphic violence, much of it the result of miniaturized smart munitions designed to take out individuals, and the result is a sci-fi fairy tale of a selfish man becoming selfless, of the masses finding what the wealthy had been enjoying for some time, eternal life.

In a med bay, not even the blown off lower part of a man’s head is immune from repair. As long as the brain is ticking and the body sufficiently intact, tissue can be repaired.

As with “District 9,” Blomkamp maintains control of CGI. It exists to enhance the story, not supplant it. And, as with District 9, the South African director likes to blow apart bodies.

“Elysium” tries to, and at the end, succeeds in tugging your heart. Its plot pulls you through the sometimes choppy story-telling.

But, the film’s real strength is the vivid portrayal of lives differentiated by access to money, health care included.

When the most recent United Kingdom royal was having a baby, she had it at an exclusive hospital with, no doubt, the best doctors and technology at her side.

The frenzied attention television and Internet paid attention to the birth in pristine conditions was appalling.

So, while the globe was fed imagery of a hospital in a fashionable neighborhood of London, I was wondering what it was like to give birth in a Syrian refugee camp on the border with Lebanon or Turkey or Jordan.

The precursors to med bays are here, now. Welcome to Elysium 2013, if you can afford it.

Del’s take

Mladen was right about one thing: “It’s tough to criticize a movie where the poor and luckless prevail,” … But that’s precisely what I intend to do. I found “Elysium” to be a simple-minded polemic about class warfare, a story that has been told more skillfully and entertainingly many times since the dawn of storytelling.

“Elysium” is a contrast in extremes. Reality as we know it is black, white, and all the shades in between. That quality is missing from Blomkamp’s stark vision of the future. What’s good is deliriously utopian, and what’s bad is worse than awful. As a result, it’s hard to take any of it very seriously.

Mladen has given you the basics of the setting, but I’ll elaborate: Earth has indeed been overrun by poverty, crime and illness, but it’s worse than that. Los Angeles is a slum built on a garbage dump, a Third World shantytown where even the basics of infrastructure don’t exist. People are subjugated by a violent police force of androids who arbitrarily beat and arrest people for minor infractions. Even Matt Damon’s parole officer, a robot, threatens him with arrest for being sarcastic (one of the film’s sparse light moments).

Then you have Elysium, the orbiting torus where the grass is green, every home is a mansion, and the citizens possess a gentility conveyed by wealth, status, and comfortable living, abetted by their medical bays that can cure every disease by simply “re-atomizing” the person’s cell structure. I’ll bet the folks behind Obamacare would like to get their hands on that one.

The price for admission is money, something the unwashed masses don’t possess. So in a crude parable of illegal immigration, people pay smugglers to get them aboard Elysium.

Except it isn’t a better life these people are seeking. It isn’t freedom from tyranny, clean water, fresh air, and opportunities to improve themselves that drive these people to Elysium. It is: health care.

Don’t get me wrong. Health care is important, especially when you’re terminally ill, as is Damon and the daughter of his former love interest. But in the sweep of human motivation, where empires hang in the balance, isn’t health care a tad farther down the list behind freedom and hope?

I’m not buying it. I’m not buying that rich people are evil, as the film seems to suggest. For every snooty scion who was born with a silver spoon in his mouth, there’s another fellow who earned his wealth by coming up with a better idea and working his backside off to make it happen. For every rich snob who looks down his nose at folks in the lower tax brackets, there’s a Warren Buffet or Bill Gates who uses his wealth to better mankind.

Nor am I buying that people less financially endowed are hapless victims, doomed to suffer the whims of the wealthy. In fact, I find it insulting Blomkamp thinks so little of us. In “Elysium,” people who try to better their lives are beaten into submission, which serves neither the rich nor the poor. It doesn’t make any sense.

My biggest gripe with “Elysium” is it ignores the real problem. The film asks, “Wouldn’t life be better if the poor had access to the same level of health care as the wealthy?” I ask, “What about overpopulation?” “What about violence?” “What about pollution?” “What about all the awful oversights and neglected problems that caused the earth to become a foul wasteland?” All the health care in the world amounts to nothing if humanity is starving, living in a toxic environment, and deprived of hope.

In “Elysium,” the answers are simple. In the world I inhabit, they are far more complex. I could wish for a utopian fantasy, but that’s all it would be: a fantasy.

I’d rather my stories offer hope in a way that’s believable and realistic. “Elysium” offers neither.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical editor. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.