Del and Mladen review ‘The Haunting’

Image courtesy of MGM.

“The Haunting” Starring Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn, and Lois Maxwell. Directed by Robert Wise. 1 hour, 52 minutes. Rated G. Shudder.

Del’s take

The opening paragraph of Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House,” upon which “The Haunting” is based, may be the finest paragraph of fiction ever written:

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

That paragraph sets the bar for excellence in writing. To match that standard of excellence in another medium, a movie, represents a challenge almost as frightening as the story itself. Robert Wise almost succeeded with “The Haunting,” a scary, atmospheric adaptation of Jackson’s novel released in 1963.

To critique a movie 58 years after the fact seems unfair. Times, people and technology change. By today’s standards “The Haunting” looks silly and shrill. But strip away years of desensitization, computer-generated movie effects and a few evolved cultural standards and “The Haunting” becomes a terrifying excursion into the unknown.

The story is about Eleanor (Julie Harris), in every sense an “old maid” to borrow an expression from that time, who yearns to escape her past. She spent the better part of her adult life caring for her disabled mother and carries a great deal of guilt for not answering her mother’s call for help the night she passed away. When she is invited to participate in a paranormal experiment at Hill House by an anthropologist, Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson), she takes the family car against her sister’s wishes and drives off into the New England countryside. At Hill House she is joined by a purported psychic, Theodora (Claire Bloom) and young Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn) who is due to inherit the house. The four are besieged by spooky goings-on, including things that go bam bam bam in the night, and ultimately must decide if these are actual events or if they have been primed by the house’s menacing ambiance to imagine them.

Both the book and movie present a question about ambiguity – are there really ghosts at Hill House, as events would suggest, or is poor Eleanor, driven near to madness by a life of caring for her demanding mother while her sister and family go about their lives with purposeful ignorance, simply imagining the voices, loud noises, and sinister airs of that rambling Victorian mansion? One thing is certain: Eleanor is desperate for attention and Hill House gives it to her, and while she seems to recognize the poisonous consequences of that attraction she doesn’t seem to care. She wants to be wanted and she never wants to leave. Hill House has become her lover.

“The Haunting” shows its age with voiceovers to communicate the neurotic internal monologues of Jackson’s protagonist, and quick zooms to suggest a ghostly presence pounding at the bedroom door. A more subtle approach would have more effectively conveyed Nell’s escalating emotional tension (see Jack Clayton’s 1961 production of “The Innocents”). We can also assume a modern audience would not sit still for the slow pacing. Other efforts – Jan de Bont’s 1999 iteration, or the recent Netflix mini-series loosely based on Jackson’s novel – reflect a more modern approach, although one could argue they were not nearly as scary as the Wise production as the novel’s menace is communicated by nuance and implication, not monsters jumping out of closets.

It might not be possible for any filmmaker to successfully capture all the dark corners of “The Haunting of Hill House,” but of the efforts so far, the Wise version most faithfully represents Jackson’s acclaimed book. It is not supremely excellent, like Wise’s 1951 effort “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” but it’s spooky as hell and well worth the nearly two hours of viewing time.

It deserves an A-.

Mladen’s take

A-, Del?

Have you already eaten too much corn candy in anticipation of Halloween?

Has the lingering sugar high distorted your ability to review a movie accurately?

C, Del. “The Haunting” is a C. The film is somewhat entertaining shlock. It’s shlockiness can’t be excused because it was made in 1963.

“Nosferatu” was released in 1922. Still bone chilling. Still eerie.

“Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” 1956. Still ghastly. Still gruesome.

“Psycho” psyched audiences in 1960. Still oedipally demented. Still remembered.

“The Haunting” hovers on just this side of watchable.

“The Haunting” is pinned to an emotionally traumatized person as is “Psycho.” Eleanor, like Norman, can’t help herself. That’s where the similarity between the two films ends.

“Psycho” pulls a stunner at the end. Norman turned victimhood into rage, disorientation, and remorselessness potent enough to rationalize murder. All that “The Haunting” does is keep Eleanor a victim to the disappointing end. First, she is mistreated as a child by her family. Then she’s mistreated as an adult by the diabolical house that also stars in “The Haunting.” Pathetic.

Norman is malevolent. Eleanor mews.

“The Haunting” has some merit. The movie mocks fire-and-brimstone Christianity. It allows for the possibility of the paranormal.

The movie has a couple of solid horror moments, too. Who’s holding Eleanor’s hand during a nightmare? Couldn’t have been Theodora. She was sleeping on the other side of the bedroom. There’s the doorknob and restless door. Both scenes are decent creepiness left to the imagination.

The film’s story is coherent. The first-person exposition pushing “The Haunting” along not too annoying.

The soundtrack would have been better suited for a sci-fi movie of that era rather than a horror flick. Once you’ve heard the simple high key tapping of the piano in “Halloween,” it’s tough to withhold comparison to other horror films no matter the year they were made.

The men in “The Haunting” were dressed as stereotype required. Tweed for anthropology Professor John and a fine jacket with some sort of emblem on the breast pocket for playboy capitalist Luke. Costume design for the ladies was appropriate, as well. Eleanor wore poofy 1950s dresses with flared skirts and sufficiently tight bodices to silhouette perky breasts. Theodora, and I believe this was done to show defiance of social norm and fit her character, wore black, including slacks. She, like Eleanor, was nicely sculpted.

C, Del.

And, this is the finest opening paragraph in fiction:

“Call me Ishmael. Some years ago – never mind how long precisely – having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.”

The finest opening sentence in any paragraph of any fiction book written is:

“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

Image courtesy of GPA Productions.

“This Is Not a Test” Starring Seamon Glass, Thayer Roberts, Aubrey Martin, Mary Morlas, Michael Greene and others. Directed by Frederic Gadette. 1 hour, 13 minutes. Unrated. Streaming on YouTube, Internet Archive.

Plot synopsis: A sheriff’s deputy sets up a roadblock on a lonely mountain road early one morning after receiving word of a possible nuclear attack. Soon several motorists gather at the checkpoint and must work together to save themselves.

Are there spoilers in this review: No.

Del’s grade: C-

—

Del’s take

The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists has published a Doomsday Clock, a metric to measure the risk of nuclear war, since 1947 when the clock was set to 7 minutes to midnight.

In 2024 that clock was set to 90 seconds to midnight. Given recent events in Ukraine, Gaza and Israel-Iran, 90 seconds is not only prudent but generous. It reminds those of a certain age that while the Cold War may have been waged 60 years ago, history has an odd way of repeating itself when humanity takes its eye off the ball.

A number of movies from that era reflect the national angst over atomic warfare, movies like “On the Beach,” “Fail Safe” and “Doctor Strangelove.” Add to that cinematic paranoia the 1962 film “This Is Not a Test,” a low-budget production that comes nowhere near the quality of a “Fail Safe” or “Doctor Strangelove” but serves one useful purpose, that of cautionary tale. It’s just not the “cautionary” you might expect.

“This Is Not a Test” was filmed in 1962 in Los Angeles County. Because none of the actors are known, they aren’t listed in the credits. No release date was given, but the studio was listed as GPA Productions.

How is the movie cautionary?

Apart from the obvious – that nuclear war is bad – it serves as a reminder to those who would take us back to the “good old days” (Are you listening, MAGAts?) that those times weren’t really all that good. Watching “This Is Not a Test” in 2024 shows us how far we’ve come as a society, and how far we’ll fall if we give in to the forces of ignorance and hate that would turn back the clock, in this case toward a social doomsday.

In “This Is Not a Test” the characters exhibit blind obedience to and trust in authority, embodied by the sheriff’s deputy, who over the course of the film evolves into a cruel autocrat. The motorists, i.e. “voters,” follow his commands without complaint or question, handing over their car keys and unloading a truck to use as a makeshift bomb shelter. I’m hard pressed to say people of today would behave like that given the sizeable number of voters who would entrust their freedoms to a criminal and traitor. But at least some of us have grown as human beings over the years.

Women are treated like property. That was often the case in movies from this period, but in “This Is Not a Test” women operate almost exclusively as instruments of male dominance and facilitators of their own downfall. A wife cheats on her husband with another man and the husband meekly skulks away. One man wins, another man loses, and the woman? She means no more to the story than a knife or a gun, used to achieve those ends.

Booze unloaded from the truck becomes a symbol for disrespect, not only for the deputy’s authority but for human decency itself. Those who consume it are depicted as morally bereft and unworthy of salvation.

And then there’s cruelty to animals, horrifying by today’s standards. In one scene a mentally ill man destroys crates carrying chickens and hurls live birds into the ground. In another scene the deputy chokes a woman’s poodle to death because it’s using up all their oxygen. Animals don’t even figure into the equation of life.

So yeah, the “good old days” weren’t really all that good, and while I understand that when people yearn for the past they’re talking about gas that cost 30 cents a gallon or Momma’s homemade biscuits, they need to remember there were other things about the past that weren’t so great, and maybe what we have today ain’t so bad.

“This Is Not a Test” is not particularly well written or acted, and it doesn’t measure up to those other movies I mentioned. But it’s useful in showing us just how much we’ve grown as a society, and how far we’ll fall if we turn the clock back to the doomsday of the past.

I give it a C-.

Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and writer.

About the author:

Del Stone Jr. is a professional fiction writer. He is known primarily for his work in the contemporary dark fiction field, but has also published science fiction and contemporary fantasy. Stone’s stories, poetry and scripts have appeared in publications such as Amazing Stories, Eldritch Tales, and Bantam-Spectra’s Full Spectrum. His short fiction has been published in The Year’s Best Horror Stories XXII; Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine; the Pocket Books anthology More Phobias; the Barnes & Noble anthologies 100 Wicked Little Witch Stories, Horrors! 365 Scary Stories, and 100 Astounding Little Alien Stories; the HWA anthology Psychos; and other short fiction venues, like Blood Muse, Live Without a Net, Zombiesque and Sex Macabre. Stone’s comic book debut was in the Clive Barker series of books, Hellraiser, published by Marvel/Epic and reprinted in The Best of Hellraiser anthology. He has also published stories in Penthouse Comix, and worked with artist Dave Dorman on many projects, including the illustrated novella “Roadkill,” a short story for the Andrew Vachss anthology Underground from Dark Horse, an ashcan titled “December” for Hero Illustrated, and several of Dorman’s Wasted Lands novellas and comics, such as Rail from Image and “The Uninvited.” Stone’s novel, Dead Heat, won the 1996 International Horror Guild’s award for best first novel and was a runner-up for the Bram Stoker Award. Stone has also been a finalist for the IHG award for short fiction, the British Fantasy Award for best novella, and a semifinalist for the Nebula and Writers of the Future awards. His stories have appeared in anthologies that have won the Bram Stoker Award and the World Fantasy Award. Two of his works were optioned for film, the novella “Black Tide” and short story “Crisis Line.”

Stone recently retired after a 41-year career in journalism. He won numerous awards for his work, and in 1986 was named Florida’s best columnist in his circulation division by the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors. In 2001 he received an honorable mention from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association for his essay “When Freedom of Speech Ends” and in 2003 he was voted Best of the Best in the category of columnists by Emerald Coast Magazine. He participated in book signings and awareness campaigns, and was a guest on local television and radio programs.

As an addendum, Stone is single, kills tomatoes and morning glories with ruthless efficiency, once tied the stem of a cocktail cherry in a knot with his tongue, and carries a permanent scar on his chest after having been shot with a paintball gun. He’s in his 60s as of this writing but doesn’t look a day over 94.

Contact Del at [email protected]. He is also on Facebook, twitter, Pinterest, tumblr, TikTok, and Instagram. Visit his website at delstonejr.com .

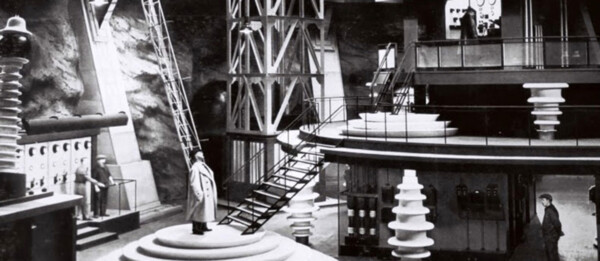

Image courtesy of United Artists.

“The Magnetic Monster” Starring Richard Carlson, King Donovan, Jean Byron, and others. Directed by Curt Siodmak and Herbert L. Strock. Writers Curt Siodmak and Ivan Tors. 76 minutes. Rating: Approved. Amazon Prime.

Mladen’s take

The Atomic Age fuses with a quark-y idea, valent script writing, and energetic performances to form the nucleus of “The Magnetic Monster.”

This elemental gem of a sci-fi movie is only 76 minutes but tells the story, and captures the fear of the unknown about radioactivity, in 1953 with panache.

There are no goofy sound effects in “The Magnetic Monster.” No overdone dumbing-down of science. There are no mad scientists, though there’s one not-too-bright physicist, in the film. There’s gentlemanly sexism. Dare not there be a woman engineer or researcher. Instead, we get a clever pregnant wife, a diligent switchboard operator, and a very athletic store clerk with one helluva body.

Now that I irritated, or is it irradiated, Del long enough by withholding a film summary, here you go.

An appliance and hardware store near a Government facility populated by “A-men” (atomic men) is magnetized. Watch out for the engineless push lawnmower with some dastardly looking blades bolting at you because you’re in the way of the pull of the polarized attractor with thirst for pure energy. A-men Drs. Jeffrey Stewart (Carlson) and Dan Forbes (Donovan) are dispatched by the Office of Scientific Investigation chief scientist to uncover the facts and cure the problem. Geiger counters tick. A man is found dead in a secret, makeshift laboratory. Off go Stewart and Forbes to get to the bottom of the incident.

The disaster that unfolds isn’t a nuclear reactor going China syndrome. The disquiet and radioactivity haven’t been released by a detonating A-bomb. “The Magnetic Monster” menace is tough to find and, when found, tough to throttle. It has to be fed to keep contained. Each subsequent feeding requires magnitudes more food and, in one instance, takes blacking out a city to provide the needed electricity. The magnetic monster grows after it eats like the Republican party bloats as it chews our democracy. That means the next monster feeding will require a bigger source of power. How long before the Earth, the solar system, the galaxy, the constellation, or the universe are consumed because the beast needs matter converted to energy to stay satiated? Oh, Einstein, what have you caused with that E=mc2 thing.

I loved this black-and-white movie for its effort to pay attention to science. For showing us wavy lines on cathode ray tubes. For demonstrating how fast those new-fangled jet-powered airplanes with straight wings can fly. For the cool, realistic explosion of a volt-injecting machine the size of a building. Thank you for at least making the effort to show that decaying metals are heavy, literally. And, dadgum, you made a block of gray material smaller than a breadbox the plausible villain.

A-, Del. “The Magnetic Monster” is an A-. Need a rationale? If you think “The Haunting” is an A-, there’s no way you can think anything less of “The Magnetic Monster.”

Del’s take

A- my ass.

“The Magnetic Monster” is at best a C. It has a couple of things going for it and a lot of things that don’t, so let’s touch on the positives first.

Number 1, forget the story. “The Magnetic Monster” is a time capsule of life in the 1950s, and while much of that life is better left to history, other aspects invoked a pleasant nostalgia for conduct and commodities that I wish existed today.

For instance, the cars. The cars are behemoths of chrome and steel, fitting of all the old nicknames – land yachts, battle cruisers and road hogs. No doubt they got crappy gas mileage and polluted the environment, but man, they sure were nice to look at. Designers back then were still trying to create art, not aerodynamically efficient blob mobiles. We all could use a little more art in our lives.

Men and women dressed for work. The ladies wore dresses and skirts with hats and gloves, while the men were clad in suits and ties. Call me old-fashioned but I think a more formal workplace dress code imparts a more formal manner of job conduct and thinking. Much of the work today seems like it was done by somebody wearing a bathrobe and house slippers.

People back then – at least in the movies – seemed more articulate. Their speech was almost patrician, with a whiff of an English accent in some – a welcome departure from the onslaught of slurred, mispronounced vulgarities we are subjected to these days.

From there “The Magnetic Monster” sleds downhill.

I’ll be first to point out life in the ’50s might have been grand for white males but not many others. Women, as illustrated in “The Magnetic Monster,” occupied the lower rungs of the corporate ladder or were kept at home in the kitchen, barefoot and pregnant. In many of these movies you don’t see people of color unless they’re about to be devoured by the title threat.

Value judgments aside, the movie makes a laudable attempt to sell a scientific plausibility, and unlike many B movies of the ’50s you never see an actual “monster.” That’s because the monster is radiation, though I was confused about the relationship between magnetism and radioactive particles that sicken and kill people.

From what I’ve read, much of the “science” in “The Magnetic Monster” is nonsense, which is not necessarily a cause for dismissing the movie. The science in virtually all science fiction movies these days is nonsense. Don’t get me started on “Star Wars.” Still, while it must have sounded impressive to an audience of that era, I heard mostly nonsense.

The movie itself relies on special effects “borrowed” from a German science fiction film of the 1930s called “Gold.” It also features brief cameos by a computer called “M.A.N.I.A.C.,” which are good for a chuckle. I’d wager an Apple Watch has millions of times more computing power. Such is the march of technology.

“The Magnetic Monster” was the first movie of a trilogy, which included “Riders to the Stars” and “Gog,” both shot in the mid-1950s.

I mentioned two things in the movie’s favor. The other is that it’s short, a hair over an hour.

I enjoyed some aspects of “The Magnetic Monster” but mostly I thought it was boring. The ’50s produced some wonderful science fiction movies – “The Day the Earth Stood Still” and “Forbidden Planet,” but this is not one of them. It’s a product of the days when people feared the atom, the Russians and the unknown. Now, we know that climate change, incompetent politicians, corporate greed and evolving pathogens present a much greater threat.

Come to think of it, I wouldn’t mind returning to those simpler days. At least in some ways.

Sorry, Mladen. C.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

Image courtesy of United Artists.

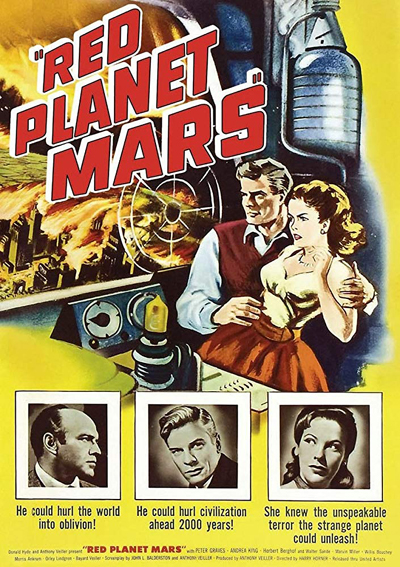

Del reviews ‘Red Planet Mars’

“Red Planet Mars” Starring Peter Graves, Andrea King and Herbert Berghof. Directed by Harry Horner. 87 minutes. Rated approved.

Del’s take

Maybe you’ve noticed I’m reviewing more Netflix, Prime and Hulu offerings these days. That’s no accident.

My MoviePass account expires at the end of this month and I won’t be renewing. When I first joined, the MoviePass deal was unbeatable – watch as many movies as you like in one month for a piddling $7. I wondered how they could make money and they didn’t. Soon they were altering the terms, adding steps and otherwise making it impossible to use your MoviePass for anything but low-rated matinees only once per week. With my new work schedule I could not have seen more than one movie per month, if that. Not much of a deal.

I subscribe to Netflix, Prime, Hulu, Shudder and Curiosity Stream. I can also choose from Vudu and Tubi TV. Needless to say I am not deprived of video content.

But finding the good ones can be a challenge. More than once I’ve searched Google for the best hidden gems on Netflix. I even have a browser extension that lets me search all the “hidden” categories Netflix does not include with its interface.

It stands to reason if I am having this problem, others likely are too. And that is the direction I am taking “Movie Faceoff.”

I will continue to review theatrical releases when I see them, and if I can ever coax Mladen away from the Great American Novel he’s working on, we’ll do them together. Meantime, I am reviewing some of the gems – and dogs – I find on my streaming services. And that brings me to this latest offering, “Red Planet Mars.”

“Red Planet Mars” is one of the most remarkable science fiction movies I have ever seen. Released in 1952 by United Artists, the movie stars a very young Peter Graves at the height of his Nordic grandeur.

The basic plot of the story is as follows: Astronomers spot what appear to be artificial canals on Mars that are transporting water from a rapidly diminishing polar ice cap. At the same time an American scientist (Graves) has established a kind of crude radio communication with the inhabitants.

At first, the communication is a simple repetition of signals sent from Earth. But Graves’ son, Stewart (Orley Lindgren) suggests transmitting the numerical value of pi to see if the Martians, if they are indeed Martians, will carry those values to the next decimal point. They do, and a dialogue is established after the cryptographers who decoded the Japanese military signals during World War II figure out how to interpret their language.

The Martians soon reveal an astonishing grasp of science, informing Graves that they live to be 300 years old, use cosmic energy as an energy source and grow enough food on a single acre to feed an entire city.

When these messages are revealed to the world, the world responds with panic and hysteria. Farmers, afraid their crops will be rendered valueless by new growing methods, demand government compensation. The oil industry freaks out (they wouldn’t do THAT, would they) and the medical community has a shit fit. The stock market collapses, riots spread across the country and the western world grinds to a halt.

Simultaneously an evil subplot is playing out. The Russians have a spy listening in on the broadcasts, a Nazi scientist who invented the technology that enables Graves to contact the Martians. The Russians intend to use the chaos as a means to subjugate the west and take over the world.

That is until the messages from Mars detour from the standard our-technology-is-superior-to-yours script and move off in a weird, unanticipated direction. Tables get turned and “Red Planet Mars” becomes something that rises above the modest aspirations of a killer B movie.

The clothes, home furnishings and cars are vintage 1952, but the giant flat-panel TV mounted on Graves’ wall is anything but, suggesting “Red Planet Mars” is set in an alternate universe.

But what’s astonishing about the movie is its willingness to address the deep issues of first contact, or the Cold War conflict between east and west. It does so in surprisingly thoughtful ways, so atypical of the ’50s B movies with their bug-eyed monsters and giant insect predators.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying “Red Planet Mars” is a “good” movie. It’s definitely a product of its time. The viewer must make a deal with himself to overlook the overacting, the offensive patriarchal viewpoints, crappy special effects and script clinkers so common of movies of that day. But do that and you may be surprised.

I will say I liked the movie a lot. It entertained me right to the end.

I would grade “Red Planet Mars” at B+ purely on the merits of its ambition.

Stone is a former journalist and author.