Del and Mladen review ‘A Life on Our Planet’

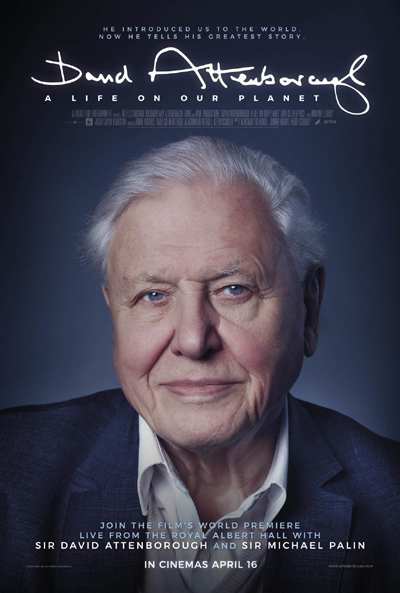

Image courtesy of Silverback Films.

“David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet” Starring David Attenborough. Directed by Alastair Fothergill, Jonathan Hughes, Keith Scholey. Rated PG. 83 minutes. Netflix.

Del’s take

The most heartbreaking moment in David Attenborough’s profound “A Life on Our Planet” takes place at about the halfway mark when we see an orangutan clinging to the shredded branch of a tree – one tree – remaining in a field of clear-cut Borneo rain forest. Surrounding this pitiful creature lies destruction – jagged stumps, mangled limbs, the earth scarred by monster bulldozers.

Gut-wrenching.

That brief snippet of video perfectly encapsulates the message of Attenborough’s documentary film about the downfall of the natural world and serves as a metaphor for the future of mankind as we greedily attack the systems that make life on Earth possible.

Attenborough has a unique perspective on this tragedy. His role as broadcast journalist and naturalist for the BBC has allowed him to see firsthand the rapid decline in animal species, the fouling of the earth and the collapse of ecosystems. As a result, “A Life on Our Planet” is “my witness statement and my vision for the future,” he says.

The first two thirds of the documentary are devoted to Attenborough’s career as a journalist-naturalist and the chilling litany of ruin and destruction he has witnessed since he began covering the “nature beat” in the 1950s. Then, the plains of Africa were covered with migrating herds of wildebeest and zebras, Antarctica was a deep-freeze of glaciers and penguins, and the oceans of the world were home to thriving coral reefs.

Compare that with today: The great herds of Africa are diminished to a trickle, with some species, like the white rhino, becoming extinct. Glacier coverage around the world has shrunk, contributing to sea level rise and the possible extinction of animals like the emperor penguin. Coral reefs are dying as the oceans heat and become more acidic.

Attenborough tries to describe the relationship that exists between mankind and nature, and how the former must be preserved if latter is to survive, then devotes the remaining third of “A Life on Our Planet” to the steps we must take to save ourselves.

In the end, “We need to learn how to work with nature, not against it,” he says.

The film is a showcase of lush visuals, both beautiful and horrific, the yin and the yang of how beautiful our world once was and could be again, and what it is increasingly becoming.

I expect his “witness statement” will fall on deaf ears.

Forgive my cynicism, but I don’t hold much hope for the years ahead. People are disconnected from nature and cannot understand the gravity of Attenborough’s message. They conflate science with some kind of political philosophy. Any attempt to educate them only hardens their disbelief. Throw in market incentives to maintain the status quo, an unswerving refusal to limit population growth, and a rampant, voracious consumerism stoked by soulless corporate entities and you reach a future that resembles a science fiction novel where masses of uneducated savages are baking in the slums of a dead world, awaiting a final war to finish off the species.

I hope that doesn’t happen. I hope “A Life on Our Planet” creates a groundswell of support for those who are trying to solve the riddles of climate change, population growth and destruction of the natural systems that give us clean water, air to breath and food to eat. I hope to see the weather return to normal, to hear a bobwhite quail calling in the morning, to see moths orbiting the porch light.

In the time it takes you to read this review, 60 average homes’ worth of rain forest will have been cut down. That’s an area roughly the size of your neighborhood, gone forever.

Better hurry.

“A Life on Our Planet” gets an A+.

Mladen’s take

Shit, Del’s correct. By that I mean he correctly assessed the quality and importance of “David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet” and the documentary’s likely impact on mankind’s environment-ruining behavior, as well as that I hate to admit Del is right about anything.

Attenborough is 93 years old. He walks with a slight hunch and his steps seem tentative, but the sparkle in his eyes, the pleasantness of his voice, and the lucidness of what he observes and says are unchanged. The Old Timer, who narrated such break-through documentaries as “Life on Earth,” “The Living Planet,” and “The Blue Planet,” should be heeded because he knows his stuff. His advice should be taken – reduce poverty to reduce deforestation, destruction of fisheries, obliteration of species; render one-third of the ocean’s littoral off limits to mankind; stopping buying so much crap.

It ain’t gonna happen, of course, as Del notes.

“A Life” makes the argument that mankind will go the way of the wild places it destroys, extinct, unless it starts preserving the atmosphere, the biosphere, and the geosphere. Attenborough’s storytelling is punctuated periodically with a counter that ticks off numbers such as the world population of humans and the percentage of wild places still left from the 1950s to today. Sobering. As the population of people grew, guess what happened to the extent of wild places? I’ll give you a clue. It’s what mathematicians call an inverse relationship.

One striking feature of the documentary might go unnoticed unless you’re paying attention. Attenborough never casts blame for the demise of nature at specific countries or leaders. Bollsanaro in Brazil, the feckless muther-f-er encouraging destruction of the Amazon, is not named. China and brutal, soulless Xi aren’t named for obliterating the country’s rivers. America and beyond-stupid Trump are not named for loosening environment preservation regulations and opening national parks and monuments to “mineral extraction.” Attenborough does use examples of sustainable activity such as agriculture in the Netherlands, if I recall accurately, to make the point mankind can have less impact on the air, land, and water while still enjoying a lofty lifestyle. To Attenborough, the environmental catastrophe facing Earth is caused by “us.” It is “our” problem. The problem can be stemmed only through global action requiring that “we” cooperate with each other.

“A Life” ends where it started, in Pripyat, Ukraine. This “atomgrad” of the former Soviet Union was the place where the people who operated the Chernobyl nuclear power plant lived. When Reactor Number 4 exploded in April 1986, all 50,000 of those people had to be evacuated. The city remains uninhabitable decades later. The radionuclides ejected into the air poisoned some of the world’s most productive land and water, crossing national borders all the way up to parts of North Europe. I assume that Attenborough chose to disregard the March 2011 Fukushima Daiichi three-reactor meltdown in Japan because that disaster is still in the early stages of unfolding.

Attenborough warns us that Earth will become Chernobyl writ planetary scale —uninhabitable for mankind — unless Homo sapiens initiates remediation now. The naturalist considers pollution and climate change significant contributing factors to the destruction of the outdoors, but not its root causes. Industrial agriculture, mining, and fishing; wanton consumerism; and human disconnection from land and sea are the culprits. He asserts we have stepped from nature and into a delusion: that the supply of Earth’s resources is infinite and that are always technologic solutions to problems caused by technology.

To illustrate there’s hope, Attenborough moves from talking about the Chernobyl catastrophe by walking through room after room filled with abandoned furniture, books, and toys to the outdoors. Large fauna (e.g., wolves, deer, and rare wild horses), the kinds of animals that end up dead or displaced when mankind moves in, are reclaiming Pripyat and so are flora. Trees are present in what were once courtyards. They compete for height with the desolate and deteriorating multi-story buildings that once housed tens of thousands of humans. It might be that vines growing up the walls of those buildings are helping them stay intact a little be longer. In Pripyat, it’s as though Nature had forgiven mankind and has started the hard task of re-nourishing the air, land, and water.

So, there it is in a visual nutshell. Attenborough shows that given enough time and space, the outdoors, and, as a consequence, mankind can recover.

“David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet” gets an A+. Watch this documentary and then go plant a tree in your yard, somewhere, anywhere. Seriously.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.