Del reviews ‘Shirley’

Image courtesy of Neon.

“Shirley” Starring Elizabeth Moss, Odessa Young, Michael Stuhlbarg and Logan Lerman. Directed by Josephine Decker. 107 minutes. Rated R.

Del’s take

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

Thus begins “The Haunting of Hill House,” a perfect novel befitting that perfect paragraph, and now blessed by a perfect dramatic rendition of the author’s life, “Shirley,” both an elegant and quixotic peek behind the curtain enshrouding horror writer Shirley Jackson.

Yet “Shirley” is not so much about Jackson as how she is perceived through the eyes of the callow wife of an instructor student who has come to Bennington College, Vermont, to learn how to be a literature professor. The young couple take room and board with Jackson and her husband, Stanley Edgar Hyman, an established professor at the college, and it is from that launching point we discover the people, and the story, and the frailties of intellect and ego, especially as they are coupled with eccentric, seemingly frail yet ultimately powerful collective of personalities.

The physical structure of the movie is as dingbatty as its subject material, flitting from reality to flashback to daydream and wish-fulfillment – muzzy, out-of-focus sequences that provide insight into the thought processes of their selectively sighted muse. Likewise for the score, which flicks from folksy twang tunes with hidden stories to slithery, slinky dream themes suggestive of everything, from the narcotic haze from which Jackson reputedly penned her stories to her repressed lust for Rose, the female half of their tenant couple.

“Shirley” threatens to become “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf” but backs away and wraps itself in something entirely different. Where it does resemble “Woolf” is in its quartet of actors and the quality of their performances. Elizabeth Moss is just stunning as Jackson, and if she isn’t rewarded with some kind of statuary, well, there is no justice. Equally stunning is Odessa Young as Professor Nemser’s wife, who arrives in the story innocent and eager to please, and leaves it with a knowing look and tic. Michael Stuhlbarg, who we last saw in “Call Me By Your Name,” is perfect as Jackson’s amoral husband, who is jealous of her talent and sets her up to fail, the covetous embodiment of the bromide, “Those who can’t do, teach.” Logan Lerman has the least screen time of the four but does a creditable job as the student professor who embraces the college monde a little too enthusiastically.

“Shirley” is for literature fans and movie fans, which means its audience will consist of a quiet few, those people against whom the silence lays steadily, as they walk, alone.

I rate it an A.

Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

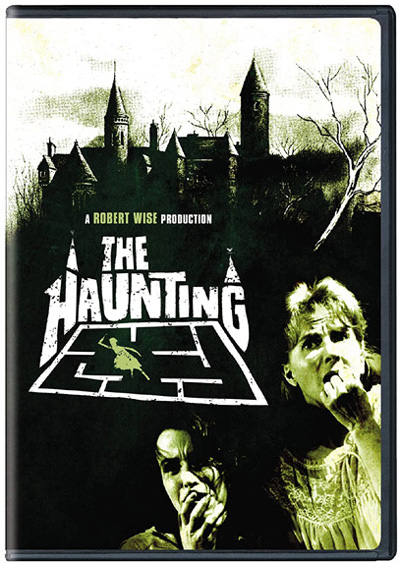

Image courtesy of MGM.

“The Haunting” Starring Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn, and Lois Maxwell. Directed by Robert Wise. 1 hour, 52 minutes. Rated G. Shudder.

Del’s take

The opening paragraph of Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House,” upon which “The Haunting” is based, may be the finest paragraph of fiction ever written:

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

That paragraph sets the bar for excellence in writing. To match that standard of excellence in another medium, a movie, represents a challenge almost as frightening as the story itself. Robert Wise almost succeeded with “The Haunting,” a scary, atmospheric adaptation of Jackson’s novel released in 1963.

To critique a movie 58 years after the fact seems unfair. Times, people and technology change. By today’s standards “The Haunting” looks silly and shrill. But strip away years of desensitization, computer-generated movie effects and a few evolved cultural standards and “The Haunting” becomes a terrifying excursion into the unknown.

The story is about Eleanor (Julie Harris), in every sense an “old maid” to borrow an expression from that time, who yearns to escape her past. She spent the better part of her adult life caring for her disabled mother and carries a great deal of guilt for not answering her mother’s call for help the night she passed away. When she is invited to participate in a paranormal experiment at Hill House by an anthropologist, Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson), she takes the family car against her sister’s wishes and drives off into the New England countryside. At Hill House she is joined by a purported psychic, Theodora (Claire Bloom) and young Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn) who is due to inherit the house. The four are besieged by spooky goings-on, including things that go bam bam bam in the night, and ultimately must decide if these are actual events or if they have been primed by the house’s menacing ambiance to imagine them.

Both the book and movie present a question about ambiguity – are there really ghosts at Hill House, as events would suggest, or is poor Eleanor, driven near to madness by a life of caring for her demanding mother while her sister and family go about their lives with purposeful ignorance, simply imagining the voices, loud noises, and sinister airs of that rambling Victorian mansion? One thing is certain: Eleanor is desperate for attention and Hill House gives it to her, and while she seems to recognize the poisonous consequences of that attraction she doesn’t seem to care. She wants to be wanted and she never wants to leave. Hill House has become her lover.

“The Haunting” shows its age with voiceovers to communicate the neurotic internal monologues of Jackson’s protagonist, and quick zooms to suggest a ghostly presence pounding at the bedroom door. A more subtle approach would have more effectively conveyed Nell’s escalating emotional tension (see Jack Clayton’s 1961 production of “The Innocents”). We can also assume a modern audience would not sit still for the slow pacing. Other efforts – Jan de Bont’s 1999 iteration, or the recent Netflix mini-series loosely based on Jackson’s novel – reflect a more modern approach, although one could argue they were not nearly as scary as the Wise production as the novel’s menace is communicated by nuance and implication, not monsters jumping out of closets.

It might not be possible for any filmmaker to successfully capture all the dark corners of “The Haunting of Hill House,” but of the efforts so far, the Wise version most faithfully represents Jackson’s acclaimed book. It is not supremely excellent, like Wise’s 1951 effort “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” but it’s spooky as hell and well worth the nearly two hours of viewing time.

It deserves an A-.

Mladen’s take

A-, Del?

Have you already eaten too much corn candy in anticipation of Halloween?

Has the lingering sugar high distorted your ability to review a movie accurately?

C, Del. “The Haunting” is a C. The film is somewhat entertaining shlock. It’s shlockiness can’t be excused because it was made in 1963.

“Nosferatu” was released in 1922. Still bone chilling. Still eerie.

“Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” 1956. Still ghastly. Still gruesome.

“Psycho” psyched audiences in 1960. Still oedipally demented. Still remembered.

“The Haunting” hovers on just this side of watchable.

“The Haunting” is pinned to an emotionally traumatized person as is “Psycho.” Eleanor, like Norman, can’t help herself. That’s where the similarity between the two films ends.

“Psycho” pulls a stunner at the end. Norman turned victimhood into rage, disorientation, and remorselessness potent enough to rationalize murder. All that “The Haunting” does is keep Eleanor a victim to the disappointing end. First, she is mistreated as a child by her family. Then she’s mistreated as an adult by the diabolical house that also stars in “The Haunting.” Pathetic.

Norman is malevolent. Eleanor mews.

“The Haunting” has some merit. The movie mocks fire-and-brimstone Christianity. It allows for the possibility of the paranormal.

The movie has a couple of solid horror moments, too. Who’s holding Eleanor’s hand during a nightmare? Couldn’t have been Theodora. She was sleeping on the other side of the bedroom. There’s the doorknob and restless door. Both scenes are decent creepiness left to the imagination.

The film’s story is coherent. The first-person exposition pushing “The Haunting” along not too annoying.

The soundtrack would have been better suited for a sci-fi movie of that era rather than a horror flick. Once you’ve heard the simple high key tapping of the piano in “Halloween,” it’s tough to withhold comparison to other horror films no matter the year they were made.

The men in “The Haunting” were dressed as stereotype required. Tweed for anthropology Professor John and a fine jacket with some sort of emblem on the breast pocket for playboy capitalist Luke. Costume design for the ladies was appropriate, as well. Eleanor wore poofy 1950s dresses with flared skirts and sufficiently tight bodices to silhouette perky breasts. Theodora, and I believe this was done to show defiance of social norm and fit her character, wore black, including slacks. She, like Eleanor, was nicely sculpted.

C, Del.

And, this is the finest opening paragraph in fiction:

“Call me Ishmael. Some years ago – never mind how long precisely – having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.”

The finest opening sentence in any paragraph of any fiction book written is:

“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.