The history of design, from cave walls to hog trough

Try to relax.

We should have a conversation, you and I, about something we have in common. I’ll try not bore. But promise you’ll read this. It won’t hurt … not for long.

What we have in common is an interest in newspapers, and design, and a curiosity about the future. But first, let me set the stage. …

In the Beginning

When I laid out my first news page we sketched our grids on cave walls by firelight and the new hire who did not know to keep moving was snapped up by lizards the size of corporate logos on a Times Square message board which is how the layout style known as “minimalism” came into existence. …

OK. Would you believe we wrote our stories on the blade of Abraham Lincoln’s shovel and slogged six miles Donner Party-style through hip-deep snow to reach the office where sometimes out of necessity we devoured the Lifestyle editor, and our “health benefits” amounted to a Flintstones chewable. …

No?

The truth, then, as my fading memory will allow.

I laid out my first newspaper page in 1979. Computers were so new that none of us realized the TV-like object on our desk was not a “computer” at all but a “terminal,” slaved to a machine which brooded in a special room, HAL-like, plotting the downfall of civilization. God help us if the temperature in that room rose above a bracing 68 degrees – we might spend the rest of the night shouting the news from a street corner as the machine choked on its fumes. (This actually happened, so don’t shake your head.)

Those of us affiliated with The Associated Press received photographs over something called a Laserphoto receiver which regular jammed, scratched pictures, or the guys in Sports would never change the film despite receiving an unfair number of pictures, which meant on Sunday afternoon there would be three photographs in the tray instead of the required 150, and of those three, two would be mug shots of forgettable celebrities like Charo and the other would be a weather map. You’d get the machine fixed in time for 150 football photos to spew forth.

We laid out our pages on yellow “dummy” sheets, which often referred to the person using the sheet. The drawing of dummy sheets became an art itself, much the way doctors write prescriptions. It was a brave (but mostly foolish) copy editor who approached his or her dummy sheet with an ink pen.

Once the page was drawn, we wrote our headlines and dispatched our copy to an electronic typesetter, often forgetting to include the markup commands (think HTML) which set the text in body copy format. The result was something called Texas Agate – a 50-inch story set in 36-point Helvetica could chew up a $15 roll of film in about two seconds flat. In 1979, $15 was over half a day’s pay.

The culmination of this chaos was a pile of film that was run through a waxer, and a battle with Sports over which person in the Production Department took his or her razor blade, trimmed off all the descenders on your headlines and “built” your page. We had our surgeons and our butchers, and again God help the copy editor who was out of favor with the “backshop.” He or she ended up with Ol’ One Thumb, who routinely sliced off various body parts while trying to get the Letters to the Editor evened out.

You will never see any of this hanging in a museum, but trust me: The entire process, start to finish, was art as art will ever be. Its practitioners were artists, and its audiences were patrons of the arts.

Times and technology change, and this is not a sentimental lament for a bygone era because frankly, the copy editor is a much more powerful creature today than in the past. Still, a Brave New World of design, and journalism as a whole, threatens. …

Viva la revolucion

The early 1980s brought a new lifeform into existence:

The page designer.

The distinction between layout and design, and copy editor and designer, is one that eluded most newspapers then, and probably many newspapers today. Simply put, the people who decided how pages look were copy editors who followed a few basic rules of layout – don’t bump heads, don’t tombstone, don’t bump art – and concentrated mostly on headline accuracy, rooting out garble in wire copy, and deadlines. Appearance was a nice but not essential icing on the cake that was tomorrow morning’s edition.

They didn’t make much money. Ho ho ho, at least that hasn’t changed.

But other advancements – the technology of computers and scanners, coupled with an increasing sensitivity to non-traditional ideas like “marketing” and “business” – threw open the musty doors of objectivity, actual journalism, and attention to detail. What spellcheck couldn’t catch, the public needn’t worry about either.

If you detect a whiff of sarcasm, please continue reading. The point will eventually be drawn.

Shot Number 1: Color emerged from the primordial ooze of ink.

At first, it was “spot” color – a single, primary color used on borders and boxes, or the occasional tint block, carefully laid down with “screens” which had to be carefully aligned so the dot patterns wouldn’t produce unintended paisley print. A sports editor I knew was fond of these tint blocks and often used a bright magenta for the top story, an eye-peeling yellow for the middle and a rich, velvety cyan for the bottom story. We called these “Marvel Comics pages” – no insult to Marvel Comics intended.

Then, “process” color in photographs began to appear with increasing regularity.

And then, the shot that was heard ‘round the world: a little thing called USA Today.

We laughed at USA Today. Actually, what we did was “laff.” We laffed at the tiny stories that carried no depth. We giggled at the goofy graphics with the little men marching up the spires of a bar chart. We shook our heads at the profligate use of color, in everything from nameplates to graphics to photographs. We laffed and laffed, and predicted doom for this amazing waste of money and talent.

But as the national attention span grew shorter and shorter, we tried to emulate USA Today, or better, improve it, because while nobody outside of Gannett High Command would have admitted it at the time, all that color, and all that artwork, and all that copy did look kinda neat. So we hired artists and bought expensive laser scanners and set aside entire pages for single stories. …

And it was somewhere around that moment when “layout,” in a DaVincian spark of revolution, became “design.” At least that’s the way it was for us.

Brave New World

The march forward has carried us to the here and now, where I exist in a continuous state of slack-jawed amazement. We have our own snooty club, the Society for News Design, with thousands of members who live and work everywhere in the world. We have computers on our desks, not terminals, and each one of these plastic prima donnas can do more, in less time, than a hundred of those hulking, AC-sucking brutes back in 1979. We dummy our pages electronically, grabbing photographs from electronic archives that exist thousands of miles away. We print them in perfect register at higher resolutions, and it happens instantly – unless the damn machine crashes, or Ol’ One Thumb forgets to load the image setter with film (she’s cross-training for a job in Sports).

And were this not sufficiently drool-inducing, we stand on the edge of another revolution, (to borrow one of the hateful buzzwords beloved by the Orwellian Mass Mind that hangs over us all like an old-fashioned woodcut of a smiling man on the moon) a “paradigm shift” which either threatens or promises – your choice here – to change utterly the way we find out if it’s gonna rain tomorrow.

The traditional (and some might say static) venue of print on paper is about to give way to the active and adaptive and infinitely flexible and dynamic World Wide Web, and to quote somebody, I don’t know who, “Things will never be the same again.”

Animal Farm

Change is in the air. A fresh breeze, or the stench of a hog trough.

The Web may do to newspapers what movies and TV did to theater – it may reduce print media to a small-market backwater. That’s not to say journalism will die. Stories will still need writing and editing. Photographs and video will need shooting and editing. New opportunities will arise as newspapers become like TV stations with depth, and TV stations become like newspapers with style.

Greater threats – or “changes,” to appease the PollyAnnas – face the Land of News, most seriously the increasing emphasis on the economics of journalism, the old P and L, the bottom line, the Show Me the Money or Get Outta My Face. “Just win, baby,” was the famous mission statement articulated for the NFL’s Oakland Raiders by owner Al Davis, who knew that points on the scoreboard amounted to money in the bank. And as it is with the NFL, and other houses of entertainment, so it is with print media. And with non journalists caught up in the process, newspapers, and magazines, and all the former uncorruptibles of the information world, will take on a perky new patina of irrelevancy as cash registers take over where the ink-stained wretches died off.

The Web may save journalism. Give a disgruntled old fart a digital camera, a laptop computer and a handful of megs on a server, and maybe he’ll do what the folks like the moneytenders who mishandled the Staples Center deal in Los Angeles apparently never knew:

Tell the truth.

We’ll see. We’ll see.

Meanwhile, what of the designer? What of the pica stick, the proportion wheel, the sliced-off appendages, the beautiful pages, and the information conveyed by story placement, headline size, and type font?

Think about this: Could the CD liner ever equal the album cover for “Aqualung”?

Will we rise to the surface, take a deep breath, then plunge into the Land of Click, the linear, artless, static realm of web design?

I assume that’s why you’ve read this far, and if I’m correct, then I assume you’ll continue. Be of good cheer; everything that follows is shorter, and more entertaining, and perhaps more caustic. It’s about the thing we have in common: design and its future. In order to explain my future I had to show you the past. But relax, because it’s over now and we can move on.

As we do, however, I want to you to keep an image in your mind, of the closing scene in Orwell’s “Animal Farm,” where the pigs, and the men, are sitting at the table, planning the future. I want you to constantly ask yourself:

“Which one am I?”

About the author:

Del Stone Jr. is a professional fiction writer. He is known primarily for his work in the contemporary dark fiction field, but has also published science fiction and contemporary fantasy. Stone’s stories, poetry and scripts have appeared in publications such as Amazing Stories, Eldritch Tales, and Bantam-Spectra’s Full Spectrum. His short fiction has been published in The Year’s Best Horror Stories XXII; Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine; the Pocket Books anthology More Phobias; the Barnes & Noble anthologies 100 Wicked Little Witch Stories, Horrors! 365 Scary Stories, and 100 Astounding Little Alien Stories; the HWA anthology Psychos; and other short fiction venues, like Blood Muse, Live Without a Net, Zombiesque and Sex Macabre. Stone’s comic book debut was in the Clive Barker series of books, Hellraiser, published by Marvel/Epic and reprinted in The Best of Hellraiser anthology. He has also published stories in Penthouse Comix, and worked with artist Dave Dorman on many projects, including the illustrated novella “Roadkill,” a short story for the Andrew Vachss anthology Underground from Dark Horse, an ashcan titled “December” for Hero Illustrated, and several of Dorman’s Wasted Lands novellas and comics, such as Rail from Image and “The Uninvited.” Stone’s novel, Dead Heat, won the 1996 International Horror Guild’s award for best first novel and was a runner-up for the Bram Stoker Award. Stone has also been a finalist for the IHG award for short fiction, the British Fantasy Award for best novella, and a semifinalist for the Nebula and Writers of the Future awards. His stories have appeared in anthologies that have won the Bram Stoker Award and the World Fantasy Award. Two of his works were optioned for film, the novella “Black Tide” and short story “Crisis Line.”

Stone recently retired after a 41-year career in journalism. He won numerous awards for his work, and in 1986 was named Florida’s best columnist in his circulation division by the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors. In 2001 he received an honorable mention from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association for his essay “When Freedom of Speech Ends” and in 2003 he was voted Best of the Best in the category of columnists by Emerald Coast Magazine. He participated in book signings and awareness campaigns, and was a guest on local television and radio programs.

As an addendum, Stone is single, kills tomatoes and morning glories with ruthless efficiency, once tied the stem of a cocktail cherry in a knot with his tongue, and carries a permanent scar on his chest after having been shot with a paintball gun. He’s in his 60s as of this writing but doesn’t look a day over 94.

Contact Del at [email protected]. He is also on Facebook, twitter, Pinterest, tumblr, TikTok, and Instagram. Visit his website at delstonejr.com .

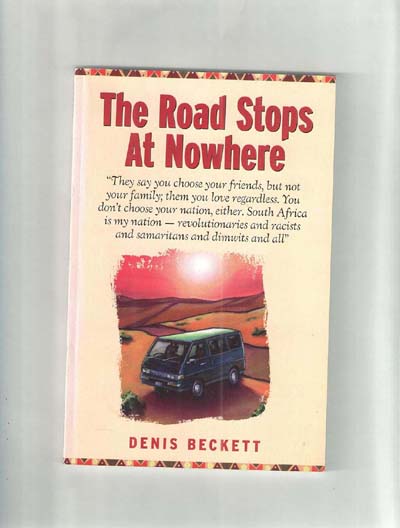

“The Road Stops at Nowhere,” by Denis Beckett, 80 pp, NDA Press, 1998.

It was our annual summer ritual: a long vacation trip by automobile.

Each of us had our roles in this undertaking: We kids were responsible for collecting our entertainment and farming out the bowl of sacrificial goldfish to Aunt Erma for possible safekeeping in her ferociously chlorinated tap water. Mom packed our bags and scoured the grocery store for provisions — forbidden treats I now realize were bribes to keep us from strangling one another in the back seat of the car and, later, in the tent. Dad was our navigator, and also our mechanic. He spent nights prior to our departure hunched beneath the hood of our ’68 Ford Fairlane, inspecting hoses and belts and fluid levels and batteries. Unlike today, 1968 America did not provide an Auto Zone on every corner. Breakdowns were matters of real concern.

But Dad was a good mechanic, and parts for the Fairlane were readily available. What breakdowns there were, we greeted with more annoyance than fuss, because that too was part of the vacation ritual.

But events could have played out much differently. Suppose, for instance, we’d been driving a Mitsubishi van outfitted with more parts from as many different sources than Dr. Frankenstein’s monster? And instead of threading our way through the alligator-and-orange-juice emporiums of Central Florida we’d been navigating a desert big as the right-handed corner of the continent?

And just suppose our government, a repressive autocracy of minority rule, were tottering on the brink of a well-deserved but unfathomable change — a rewriting of the old social order that might come about with a bang or a whimper, bringing to our lives new ways neither tested by their advocates nor trusted by their detractors.

Not exactly “What I Did on My Summer Vacation.”

More precisely, it is “The Road Stops at Nowhere,” a slender volume describing the events of a summer vacation that did not go according to plan.

When South African journalist Denis Beckett loaded his bags and his family into their Mitsubishi Starwagon and set out for the Eastern Cape for a midsummer vacation at the beach, he could not have known this simple excursion would become an odyssey of baffling mechanical breakdowns and even more baffling repair jobs, both of which occurred with fateful unpredictability in an environment that was as arid socially and culturally as it was meteorologically.

Beckett writes with humor and directness as he describes his family’s journey across the Karoo, a “timid desert” by the standards of its parched neighbors, the Kalahari and Namib. A timing chain on the Mitsubishi breaks. Then the oil pump goes. Then the pistons seize. Promised repairs go undone — not because the mechanic is dishonest. Here in the wastes, a different concept of time exists, where “Wednesday night, for sure, definite” means whenever the parts come in.

Beckett ferries his family on to Cape Town by train, intending to return for the crippled van, which has now developed water pump problems. But his daughter breaks her arm, necessitating a whirlwind introduction to the vicissitudes of South African emergency medicine.

Which is only the beginning. The Mitsubishi is bewitched with more breakdowns. The repairs are similarly afflicted. The family is smitten with more trips by train.

The vacation is in peril.

Throughout this incredible litany of bizarre and often hilarious misadventures, Beckett provides a running narrative about the political and social climate of pre-democracy, not-quite-post apartheid South Africa that both enlightens and unhinges. While most Americans, freighted with their own perceptions of racial injustice, viewed the unfolding of events in South Africa as a simple contest between good and evil, Beckett reveals the invariable shades of gray that color in any human conflict, best exemplified by this excerpt, which describes the state of racial affairs at that moment:

“South Africa lacks the normal symbols of national unity, like flag and anthem, but we at least have a slogan that applies all round. It is: `I Am Not A Racist But …’

“In town, a white woman has said there’s no work for whites. `The bosses in Johannesburg tell their managers: `We’re against apartheid so you must employ non-whites.’ Then they pay them less so they get more profits.’ Two coloureds (Indians) have told me there’s no work for coloureds: `The Boers like the blacks because they’ll work for slave wages.’ Now I’m told there’s no work for blacks: `The Boers take coloureds, who speak their language and won’t stand up for workers’ rights.’ “

While sometimes depressing, Beckett’s narrative is suffused with hope — not the drippy smarm of prime time TV network fare, but a pragmatic acknowledgement that while things were bad and may get worse, down the line they may get a whole lot better. This was, after all, pre-democracy South Africa, when idealism was slowly tipping the scales toward a day when blacks and whites would share responsibility for running the country.

While the new South Africa faces serious growing pains, Beckett neatly articulates his expectations of what is happening in his nation, and what will happen in the years to come, with this scene that takes place in an auto repair shop. The Mitsubishi lost its starter, which has just been repaired from scavenged parts by the shop’s two owners, a white man and a coloured, both of whom are named Frans:

“I am proudly presented with what one Frans calls the most bastard starter he ever saw, with portions of Ford and Toyota and Massey-Ferguson in its ancestry.”

The starter may be ugly, but it works.

Beckett has a long history of speaking out against white-only rule in South Africa, having edited the publication Weekend World, which was banned in 1977. He then managed The Voice, which faced banning orders in 1978 and 1979. From 1980 to 1990 he was owner and editor of Frontline magazine.

He now appears on “Beckett’s Trek,” a weekly television program. He also publishes a socio-political journal titled Sidelines.

With humor and pathos, Beckett writes about a nation soon to be born, and a people who must grow into democracy, and perhaps forgiveness, too.

In their struggle we see America past and present, what we have gone through, and what lies ahead — bastard starter and all.

“The Road Stops at Nowhere” is available from NDA Press, 10469 Sixth Line, RR#3, Georgetown, Ontario L7G 4S6, Canada. $10 U.S.; $14 Canada. Tel: 905.702.8600 or fax 905.702.8527. E-mail: [email protected].

Amazon: “The Road Stops at Nowhere”

About the author:

Del Stone Jr. is a professional fiction writer. He is known primarily for his work in the contemporary dark fiction field, but has also published science fiction and contemporary fantasy. Stone’s stories, poetry and scripts have appeared in publications such as Amazing Stories, Eldritch Tales, and Bantam-Spectra’s Full Spectrum. His short fiction has been published in The Year’s Best Horror Stories XXII; Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine; the Pocket Books anthology More Phobias; the Barnes & Noble anthologies 100 Wicked Little Witch Stories, Horrors! 365 Scary Stories, and 100 Astounding Little Alien Stories; the HWA anthology Psychos; and other short fiction venues, like Blood Muse, Live Without a Net, Zombiesque and Sex Macabre. Stone’s comic book debut was in the Clive Barker series of books, Hellraiser, published by Marvel/Epic and reprinted in The Best of Hellraiser anthology. He has also published stories in Penthouse Comix, and worked with artist Dave Dorman on many projects, including the illustrated novella “Roadkill,” a short story for the Andrew Vachss anthology Underground from Dark Horse, an ashcan titled “December” for Hero Illustrated, and several of Dorman’s Wasted Lands novellas and comics, such as Rail from Image and “The Uninvited.” Stone’s novel, Dead Heat, won the 1996 International Horror Guild’s award for best first novel and was a runner-up for the Bram Stoker Award. Stone has also been a finalist for the IHG award for short fiction, the British Fantasy Award for best novella, and a semifinalist for the Nebula and Writers of the Future awards. His stories have appeared in anthologies that have won the Bram Stoker Award and the World Fantasy Award. Two of his works were optioned for film, the novella “Black Tide” and short story “Crisis Line.”

Stone recently retired after a 41-year career in journalism. He won numerous awards for his work, and in 1986 was named Florida’s best columnist in his circulation division by the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors. In 2001 he received an honorable mention from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association for his essay “When Freedom of Speech Ends” and in 2003 he was voted Best of the Best in the category of columnists by Emerald Coast Magazine. He participated in book signings and awareness campaigns, and was a guest on local television and radio programs.

As an addendum, Stone is single, kills tomatoes and morning glories with ruthless efficiency, once tied the stem of a cocktail cherry in a knot with his tongue, and carries a permanent scar on his chest after having been shot with a paintball gun. He’s in his 60s as of this writing but doesn’t look a day over 94.

Contact Del at [email protected]. He is also on Facebook, twitter, Pinterest, tumblr, TikTok, and Instagram. Visit his website at delstonejr.com .