Trip to Germany: A tidy little murder factory

Dachau is a testament to the German sense of order and efficiency. The camp is a huge box surrounded by a moat and two rows of fencing. Guard towers overlook the perimeter. The interior consists of an administration building and quarters for the guards, plus row upon row of box-like plywood structures to house the inmates. Image by Del Stone Jr.

It was hot the day we came to Dachau.

The air was thin and unbreathable, the sun boring through the haze with a strange determination.

Absolutely nothing should be right with a place where hundreds of thousands of people were put to death.

Nothing was right with Dachau.

The land surrounding the camp is rich and febrile with life – lush fields of corn and greenly dark swaths of forests standing in cruel apposition to this deadly patch of ground where little more than stiff bristles of grass will grow.

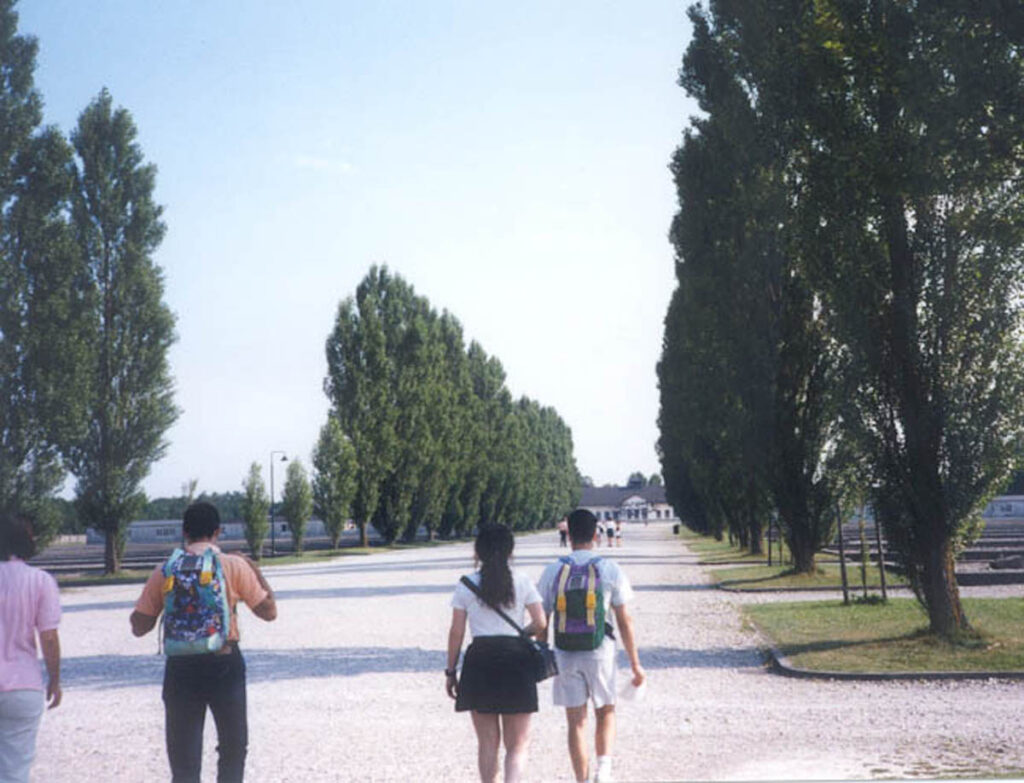

We parked the car and followed an asphalt footpath that led through a canopy of trees. Leaves swished in the wind. Cars raced by on a nearby road. Somehow, these sounds were smothered.

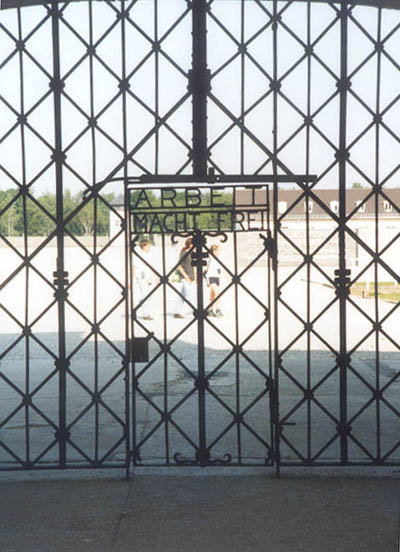

Ahead, a gate admitted us to the concentration camp.

The complex is enclosed by two rows of fences. The outermost is linked to a series of guard towers, with vast, open spaces on either side, room enough for even the worst shot in the S.S. to cut down an escapee.

A moat runs the perimeter, parallel to the fence, and then an inner fence, topped with reptilian coils of barbed-ware, finishes the camp’s security barriers.

The camp itself is a huge rectangle, maybe half a mile in length. The administration building sits at one end, a huge, C-shaped structure, low as a pill box and unlovely as a mausoleum. Fronting this is a sprawling, empty expanse – again, the mind conjures images of machine guns sweeping their deadly rattle across a field of screaming people.

The barracks lay on the other side of that expanse. Row upon row of barracks – I don’t remember how many, but only one row remains now – and it is only a reconstruction of the originals. More than 700 people were crammed into each barrack. The buildings were built of flimsy plywood. The people must have frozen in the winter and suffocated in the summer.

At the back of the camp we crossed a fresh, clear-running stream, and passed through a gate. There were two buildings here. They contained the gas chambers and the ovens.

The gas chambers were simple, block rooms, with drains in the floor and vents in the ceiling. No light entered these rooms.

The ovens were sturdy hulks of sold steel with blackened mouths, sooted by fire. They hunkered at the back of a room that lay between the gas chambers. Visitors had filled the ovens with bouquets of flowers, but the gurneys were still visible. They resembled the stretchers an ambulance attendant wheels into a hospital emergency room. The webbing sagged with the weight of all the bodies they had carried into the fire.

The administration building at Dachau has been made into a museum, where the history of the Nazi Party, and of the concentration camps, has been presented in photographs and artifacts. You can see the horrible story that unfolded there, from the clothes inmates wore to the charting of inhuman medical experiments.

But most horrible of all is the camp itself, which is laid out with a precision and efficiency that defies description. Evil is more unthinkable when it wears the face of a monster, but at Dachau the monster is no uglier than any other human endeavor.

A tidy little murder factory.

That was Dachau, on a hot summer afternoon.

This column was originally published in the Wednesday, Oct. 1, 1997 edition of the Northwest Florida Daily News and is used with permission.

About the author:

Del Stone Jr. is a professional fiction writer. He is known primarily for his work in the contemporary dark fiction field, but has also published science fiction and contemporary fantasy. Stone’s stories, poetry and scripts have appeared in publications such as Amazing Stories, Eldritch Tales, and Bantam-Spectra’s Full Spectrum. His short fiction has been published in The Year’s Best Horror Stories XXII; Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine; the Pocket Books anthology More Phobias; the Barnes & Noble anthologies 100 Wicked Little Witch Stories, Horrors! 365 Scary Stories, and 100 Astounding Little Alien Stories; the HWA anthology Psychos; and other short fiction venues, like Blood Muse, Live Without a Net, Zombiesque and Sex Macabre. Stone’s comic book debut was in the Clive Barker series of books, Hellraiser, published by Marvel/Epic and reprinted in The Best of Hellraiser anthology. He has also published stories in Penthouse Comix, and worked with artist Dave Dorman on many projects, including the illustrated novella “Roadkill,” a short story for the Andrew Vachss anthology Underground from Dark Horse, an ashcan titled “December” for Hero Illustrated, and several of Dorman’s Wasted Lands novellas and comics, such as Rail from Image and “The Uninvited.” Stone’s novel, Dead Heat, won the 1996 International Horror Guild’s award for best first novel and was a runner-up for the Bram Stoker Award. Stone has also been a finalist for the IHG award for short fiction, the British Fantasy Award for best novella, and a semifinalist for the Nebula and Writers of the Future awards. His stories have appeared in anthologies that have won the Bram Stoker Award and the World Fantasy Award. Two of his works were optioned for film, the novella “Black Tide” and short story “Crisis Line.”

Stone recently retired after a 41-year career in journalism. He won numerous awards for his work, and in 1986 was named Florida’s best columnist in his circulation division by the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors. In 2001 he received an honorable mention from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association for his essay “When Freedom of Speech Ends” and in 2003 he was voted Best of the Best in the category of columnists by Emerald Coast Magazine. He participated in book signings and awareness campaigns, and was a guest on local television and radio programs.

As an addendum, Stone is single, kills tomatoes and morning glories with ruthless efficiency, once tied the stem of a cocktail cherry in a knot with his tongue, and carries a permanent scar on his chest after having been shot with a paintball gun. He’s in his 60s as of this writing but doesn’t look a day over 94.

Contact Del at [email protected]. He is also on Facebook, twitter, Pinterest, tumblr, TikTok, and Instagram. Visit his website at delstonejr.com .