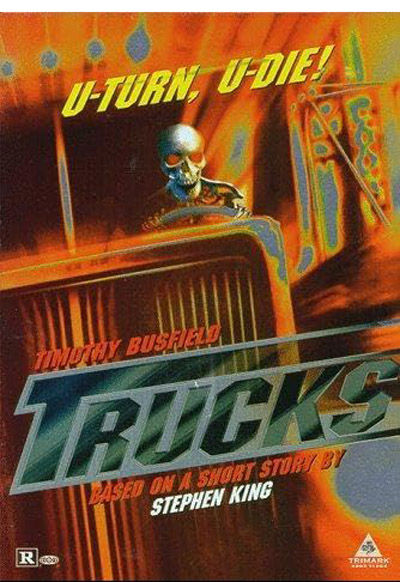

Mladen and Del review ‘Trucks’

Image courtesy of Credo Entertainment Group and USA Pictures.

“Trucks” stars Timothy Busfield as Ray, Brenda Blake as Hope, Brendan Fletcher as Logan, Amy Stewart as Abby, and others. Directed by Chris Thomson. Rated PG-13 with a 95-minute run time. See it on Amazon Prime, Tubi, Apple TV and Vudu.

Mladen’s take

To recuperate my manliness after Del forced me to watch and review “Barbie” and “Wham!,” I made him watch 1997’s “Trucks.” And, what a film it is. From its big rig practical effects to the bonkers scene involving a Tonka-looking radio-controlled toy truck, the movie plows through your disbelief and eye rolling like a convoy of rabid Teamsters through a school zone.

Here, feel free to skip to the next paragraph. Del wants a movie summary in each review, so I’m giving you one, like it or not. “Trucks” is based on a Stephen King short story. In “Trucks,” trucks come alive, herding people into crappy buildings in a dusty town not far from Area 51. The trucks terrorize the huddled humans and, when needed, run over or otherwise murder a few. The self-driving, bloodthirsty machines, who talk to each other by flashing their headlights and switching windshield wipers on and off, are animated by … I’m not sure. The victims talk about mysterious satellite dishes erected at the nearby Air Force base, aliens attracted to Earth by SETI, a stolen election for president, the contents of Hunter Biden’s laptop, and, wait, I think I’m confusing one government conspiracy with another.

“Trucks” has flaws that go unremedied. There’s no nudity. The swearing is mild. The violence is not as graphic as it could’ve been, though the fire axe-wielding hazmat suit scene in a disaster response van is pretty damn terrific. And, let’s not forget the toy truck and mailman incident that unfolds about half-way through the film. It’s imaginative. It’s ridiculous. It’s carnage laced. In short, it’s perfect.

“Trucks” also has flaws that get remedied. For example, the killer trucks are autonomous but have no way of refueling themselves. So, through much of the film, I’m like, “Stupid rednecks, sit tight until the monstrous machines run out of gas.” Then comes along our principal scared, bewildered, and desperate protagonist (“Ray” portrayed by Timothy Busfield) who notices that the trucks had chances to kill him but didn’t. Why? Why did he live while some of his fellow captives died? Well, the trucks signal the answer to him. You see, Ray is the town’s gas station owner. The machines spared Ray because they needed him to refuel them. If he didn’t, they’d splatter his son and nascent girlfriend all over the desert sand. Come on, concede that’s a clever way for the trucks (and the movie’s plot) to overcome their lack of hands with opposable thumbs to pump diesel.

Because “Trucks” is based on a King short story and King often sways toward the bleak, the film’s ending is somewhat discombobulating. But, don’t worry, the ending is nothing like the heavily traumatizing conclusion of another movie based on King’s writing, “The Mist.”

Del’s take

I was confused.

Fifteen minutes into “Trucks” and still no Emilio Estevez. What the hell was going on?

A quick dive into the Internet Movie Database disabused me of my mental fog. “Trucks” is not “Maximum Overdrive,” the cheesy ’80s-vintage scifi-horror movie directed by none other than horror author Stephen King. Instead, “Trucks” is a cheesy ’90s-vintage scifi-horror movie based on the same short story, “Trucks,” that inspired “Maximum Overdrive.” And that story was written by none other than horror author Stephen King.

That’s about as clear as my soap-scum infused glass shower doors.

I’d describe “Trucks” as a genre hybrid, falling somewhere between a classic ’50s big bug movie and a Robert Rodriguez grindhouse gorefest, Why anybody thought “Trucks” was worthy of a remake escapes me, especially when King wrote many other memorable stories – the one about the guy who drinks bad beer and turns into a giant escargot comes to mind every time I pop the tab on a can of Natty Light. But then, why are there 27 “Children of the Corn”s or 91 “Lawnmower Man”s? The answer, of course, is that Americans have no bottom when it comes to schlock.

And that’s what “Trucks” is – schlock. It’s one of those movies that’s so bad, it’s good – except “Trucks” isn’t good. It’s terrible, and Mladen owes me big time. At least when I make him watch something out of his comfort zone it’s something decent, and good. “Trucks” is a Baby Ruth bar floating in the swimming pool of moviedom. The acting is awful. The script is laughably inept. No cliché is left behind. And there are plot holes big enough to … ahem … drive a truck through. It’s like watching political aides trying to teach Ron DeSantis how to eat pudding with chopsticks. In other words, it’s a mess.

Here’s an example of the breathtaking dialogue:

Teenage girl: “Why does everybody keep dying?” (Hmmm? Could it possibly have anything to do with the fact that they’re being RUN OVER BY TRUCKS?)

Old man: “I don’t know. I’m just an old hippie.”

??????????????????????

The trucks, we are told, have been brought to life by either Area 51, a toxic gas cloud, the Earth sailing through a comet’s tail, aliens … or maybe “Trucks” is a cautionary tale, warning against the unintended consequences of electing a fascist as president of the United States and then letting him skate when his crimes become public knowledge. Either way, I think everyone involved in the movie sailed through a comet’s tail because if “Maximum Overdrive” proves that horror authors should stick to writing horror stories and not directing horror movies, “Trucks” proves that even dedicated filmmakers can sometimes screw up, and “Trucks” is a Godzilla-sized Phillips-head of a screw(up).

Mladen didn’t assign a letter grade to “Trucks” so I’ll assume he’s giving it an F. I’ll be generous and award a D- seeing as how it’s truer to the short story than “Maximum Overdrive.”

When they come out with a scifi-horror movie titled “Night of the Killer Prius,” I’m there. But “Maximum Overdrive” and “Trucks” is a two-movie convoy of 18-wheeled schlock. For a vastly superior killer truck movie, check out “Duel.” Meantime, I’ll stick to the passing lane.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and writer.

[ Main image courtesy of SplitShire at Pexels by way of a Creative Commons license ]

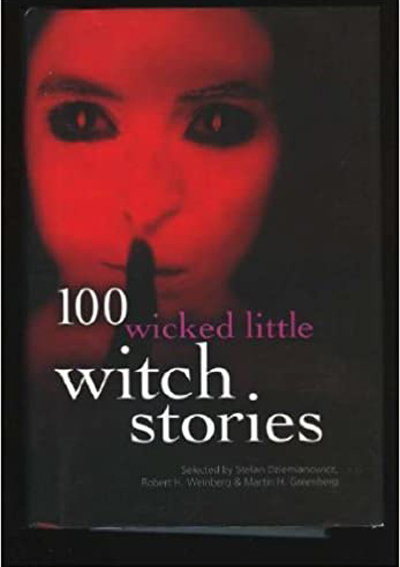

The genesis of my story, “I Feel My Body Grow,” in “100 Wicked Little Witch Stories” was simple: I wanted to sell a story to “100 Wicked Little Witch Stories.”

During the ‘90s writer and editor Stefan Dziemianowicz edited a number of anthologies for Barnes & Noble, all of them centered around very short stories. Seems publishers love short shorts, and I’m not sure if that’s because they can get more in each books or that readers prefer very short stories. As a reader I have no druthers either way, though I will pause before committing to a novelette or novella. I didn’t read Stephen King’s “The Mist” for many years because of that bias.

When I heard Dziemianowicz was editing a book of witch stories I tried to come up with something that would fit his premise. I knew nothing about witches except what I’d seen in movies or TV. I knew a couple of people who claimed to be witches but their witchhood had less to do with eye of newt and hair of bat but the whole Mother Earth and Gaia thing, which I dismissed as a New Age hippie trend.

What I wanted was a witch for the modern ages, maybe not an evil witch but one who was vengeful. I came up with just such a creature:

Cancer.

Cancer is the modern scourge. We think of it as evil though it has no conscious intent – it merely is.

But I asked: What if it did have conscious intent?

“I Feel My Body Grow” is the answer.

This is a creepy story and when I re-read it recently I was gratified to see it holds up well, from 1995 to this writing in 2023. I think it would make a terrific feature in a horror anthology movie like “Tales from the Crypt” or “Twilight Zone.”

I don’t believe “I Feel My Body Grow” will leave you lying awake tonight jumping at every sound. I do hope it stays with you.

Oh, and one more thing. This story was converted into a vlog, which is posted on YouTube. Check it out! Witchy voice and all. Follow this link.

From Amazon

“I admit that when I bought this book, I didn’t have very high expectations for it. I mean, I’d never heard of it before, but I took a chance and bought it anyway. And I loved it. The stories are all so different; some were funny, others were dark and foreboding, and some were exciting.“

– Chayleen Anderson

The witches who populate these 100 delightfully scary stories include practitioners of white witchcraft and devotees of black magic. Most are female, some are male, and a few are thoroughly unclassifiable. They can be born witches or made witches, and may mix simple love potions or volatile concoctions that threaten all we hold dear. Some resent not receiving the treatment they feel they deserve from lesser mortals; yet other witches don’t even realize that they wield any special influence at all. The many writers who take on this ever-fascinating character (so fundamentally human unlike her more paranormal, ghostly brethren) include Juleen Brantingham (“Burning in the Light”), Joe R. Landsdale (“By the Hair of the Head”), Simon McCaffery (“Blood Mary”), Terry Campbell (“Retrocurses”), Lawrence Shimel (“Coming Out of the Broom Closet”), and a coven of others.

About the author:

Del Stone Jr. is a professional fiction writer. He is known primarily for his work in the contemporary dark fiction field, but has also published science fiction and contemporary fantasy. Stone’s stories, poetry and scripts have appeared in publications such as Amazing Stories, Eldritch Tales, and Bantam-Spectra’s Full Spectrum. His short fiction has been published in The Year’s Best Horror Stories XXII; Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine; the Pocket Books anthology More Phobias; the Barnes & Noble anthologies 100 Wicked Little Witch Stories, Horrors! 365 Scary Stories, and 100 Astounding Little Alien Stories; the HWA anthology Psychos; and other short fiction venues, like Blood Muse, Live Without a Net, Zombiesque and Sex Macabre. Stone’s comic book debut was in the Clive Barker series of books, Hellraiser, published by Marvel/Epic and reprinted in The Best of Hellraiser anthology. He has also published stories in Penthouse Comix, and worked with artist Dave Dorman on many projects, including the illustrated novella “Roadkill,” a short story for the Andrew Vachss anthology Underground from Dark Horse, an ashcan titled “December” for Hero Illustrated, and several of Dorman’s Wasted Lands novellas and comics, such as Rail from Image and “The Uninvited.” Stone’s novel, Dead Heat, won the 1996 International Horror Guild’s award for best first novel and was a runner-up for the Bram Stoker Award. Stone has also been a finalist for the IHG award for short fiction, the British Fantasy Award for best novella, and a semifinalist for the Nebula and Writers of the Future awards. His stories have appeared in anthologies that have won the Bram Stoker Award and the World Fantasy Award. Two of his works were optioned for film, the novella “Black Tide” and short story “Crisis Line.”

Stone recently retired after a 41-year career in journalism. He won numerous awards for his work, and in 1986 was named Florida’s best columnist in his circulation division by the Florida Society of Newspaper Editors. In 2001 he received an honorable mention from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association for his essay “When Freedom of Speech Ends” and in 2003 he was voted Best of the Best in the category of columnists by Emerald Coast Magazine. He participated in book signings and awareness campaigns, and was a guest on local television and radio programs.

As an addendum, Stone is single, kills tomatoes and morning glories with ruthless efficiency, once tied the stem of a cocktail cherry in a knot with his tongue, and carries a permanent scar on his chest after having been shot with a paintball gun. He’s in his 60s as of this writing but doesn’t look a day over 94.

Contact Del at [email protected]. He is also on Facebook, twitter, Pinterest, tumblr, TikTok, Ello and Instagram. Visit his website at delstonejr.com .

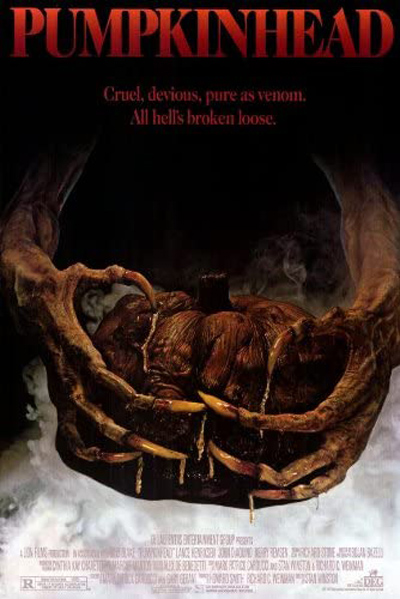

Image courtesy of MGM/UA.

“Pumpkinhead” Starring Lance Henriksen, Jeff East, John D’Aquino and Florence Shauffler. Directed by Stan Winston. 86 minutes. Rated R. Amazon Prime.

Del’s take

They had me at the cicadas.

If I remember the South for anything it will be sluggish July afternoons, when the chore of taking a breath is like sucking a wad of steamed broccoli into your lungs, as cicadas hidden within the needles of longleaf pines screech and screech and screech screech screech. According to folklore the infernal bugs “hibernate” underground for 17 years until one night they awaken to scale a nearby slash pine – yes, it’s always at night – squeeze from their shell, pump up their wings and fly away to enjoy a brief yet incandescent third act of noisy fornication.

That rhythmic screeching, like chalk chalk chalk on a blackboard, is stamped onto my brain. So, when I heard it used as an audio effect in “Pumpkinhead” I knew the story was taking place somewhere below the Mason-Dixon, where the ever-increasing heat has baked the brains out of everybody who lives there, transforming them into Trump supporters.

The horror.

I didn’t let that stop me from enjoying “Pumpkinhead’s” other charms. The movie, which was released way back in 1989, has become a cult favorite despite early panned reviews. The directorial debut of special effects wizard Stan Winston, “Pumpkinhead” inspired a straight-to-video sequel, two made-for-TV sequels, a comic book from Dark Horse and even a video game.

Plus, it stars one of my favorite underrated actors, Lance Henriksen, who appeared in several James Cameron movies along with Bill Paxton and Jeanette Goldstein. He brings just the right touch of doom to his role as grieving father Ed, who sets off the horrific chain of events in “Pumpkinhead.”

The story goes like this: As a young boy, Ed witnessed a man being killed by a monster and knows that with the help of the right people, he can summon a demon to avenge the death of his young son Billy, who was accidentally run over by a dirt bike rider who had come to the back woods with his friends to party.

With the guidance of Haggis (Florence Shauffler), a crone who lives in the deep woods, Ed summons the Pumpkinhead demon and sets it loose on the teens, choosing to disregard her warning that Pumpkinhead is as dangerous to those who evoke its presence as those intended to receive its wrath.

The result is well-choreographed and photographed slaughter that follows a predictable path with only a slight deviation there at the end. Lessons will be taught and for some, learned, while for others there may be no moral to this story.

“Pumpkinhead” is one of those fun B movies that works if you can get past the threadbare writing and horror movie clichés. It calls forth an eerily gothic atmosphere you have never seen from Henry James or even V.C. Andrews. Henriksen delivers his patented emotionally wounded performance – you can’t help but sympathize with the guy, even if events leading up to his actions follow a corny, well trodden horror movie trail.

The real star here is the Pumpkinhead demon, which I thought worked very, very well. It’s a movie monster you haven’t seen before and in ways reminded me of the atavistic horror of “Alien.” It produces a similar quality of dread, even if the cornpone story doesn’t.

“Pumpkinhead” has lots of gross and gore, which should forestall whiny lectures from Mladen about R ratings and blood spatter. It’s a necessity for any serious horror movie collector or fan. Watch it in 2021 about mid-October, after the real horror of 2020 has mostly faded from memory.

I give it a B.

Mladen’s take

Del and I have been friends for a long time. And, still, he’s simply unable to judge the depth and breadth of my intolerance for inadequate moviedom mayhem, violence, and cussing.

“Pumpkinhead” is a good movie. I throw it an A- for the superb creature effects, which offset the movie’s quasi-“Deliverance” vibe. However, there are no dismemberments or intestines spilling from sliced abdomens. Shoot, plenty of blood is spilled, but no depictions of arterial pulse squirting. Sure as hell there is very little swearing, if any, that I recall and there is definitely no damned nudity. So, forgive me Del, but I’m whining, anyway, though, really, it’s closer to satisfied grumbling because the “Pumpkinhead” plot is solid.

In fact, I had little trouble overlooking the plot’s trigger, a grieving father mischaracterizing the city slickers’ accidental mistreatment of his geeky son. What unfolds is horror movie commentary on the ruin that engulfs those seeking revenge. For, you see, Ed the father becomes entwined with the monster he unleashes. When Pumpkinhead kills, Ed feels it.

—

Quick, what excellent recent movie uses the same type of symbiotic relationship between man and beast as an integral part of the story? Answer: “Sputnik.”

—

It’s Pumpkinhead who has me enamored by this late 1980s film. This is a lovingly, carefully, patiently, and nicely crafted terror animal. The only non-practical, i.e. without makeup, and non-mechanical visual effect in the movie is blurred and swaying filmography showing Ed sensing that Pumpkinhead is about to strike.

Pumpkinhead, by the way, is a tall guy in a costume. The creature is a decaying pink and skeletal. It has no hair, a tail, claws for hands, pseudo-hooves for feet, and long bony protrusions from the shoulders. Its legs at the knees bend like a heron’s, forward, if I recall accurately. Its teeth are long, crooked, and cracked and eyes white, opaque, and all-seeing. Pumpkinhead is a conjured beast, maybe risen from the fires of hell, making a living in the material world. Pay attention to the shrunken monster’s face when it’s re-buried.

Pumpkinhead’s interaction with reality as we understand it is very nicely executed in its namesake film.

There’s our nightmare walking past a window as though taking a leisurely stroll while the kid killers inside the cottage talk about what to do. When Pumpkinhead prowls through the house, it ducks beneath doorways. It swivels and tilts its head to listen. And, Pumpkinhead has no trouble looking straight at you while contemplating, I imagine, what to do next. It kills your ass and then hangs around for a moment to watch the reaction of your friends. There are no rampages. Just a methodical hunt to pick off the offending, big-hair youths. Wait till you see how the monster decides to handle a rifle. Pumpkinhead is scary as hell because it’s very human.

To me, Pumpkinhead has a subtler charisma than the Xenomorph in “Alien,” more natural finesse than the Predator in “Predator,” and a finer malevolence than Freddy in “A Nightmare on Elm Street.”

It’s my hope that no dumbass 21st century producer decides to re-make “Pumpkinhead.” This is a story and a monster that stand on their own. The beast borne of revenge shouldn’t be risked by a crappy re-do.

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical editor. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

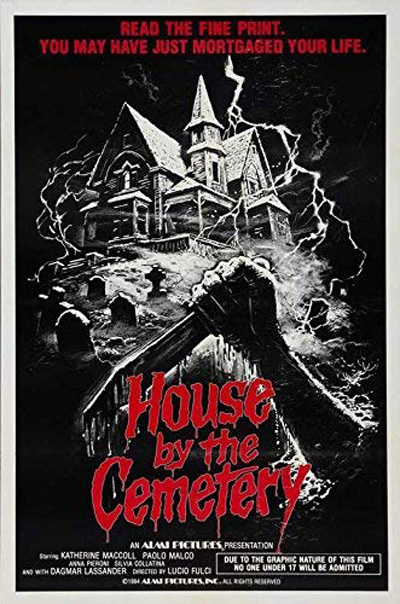

Image courtesy of De Paolis In.Co.R. Studio.

“The House by the Cemetery” Starring Catriona MacColl, Paola Malco and Ania Pieroni. Directed by Lucio Fulci. 86 minutes. Not rated.

Del’s take

“The House by the Cemetery” is a film only a horror purist could love, and love it they do, in gushing online paeans that celebrate its blood-drenched genius. Written by legendary screenwriter Dardano Sacchetti and directed by the Godfather of Gore, Lucio Fulci, “House” is itself a paean to violence, splashing its audience with viscera, maggots, and other gory tropes of Italian horror cinema.

It is part of Fulci’s Gates of Hell trilogy, which also includes “City of the Living Dead” and “The Beyond” – entries in a catalog of horror movies, spaghetti westerns and comedies that make up the erstwhile communist agitator’s body of work. Fulci passed away in 1996 due to complications from diabetes after suffering a life nearly as tragic as his horror films, but he has developed a cult following over the years and many of his fans rate “The House by the Cemetery” one of his best works.

The story is about a young academic, Dr. Norman Boyle, who brings his wife and son to a small, rural town so that he may resume the work of a colleague, identified only as Dr. Petersen. Petersen was researching the notorious Dr. Freudstein, a 19th century medical practitioner who allegedly conducted forbidden experiments resulting in disfigurement, death and, shall we say, supernatural complications. During his investigation, Petersen inexplicably loses his mind, kills his girlfriend and hangs himself from the rafters of the town library. Now Dr. Boyle has arrived to finish Petersen’s work. He has even moved his family into the house that was previously occupied by Dr. Freudstein.

The Boyles are joined by Ann, ostensibly a babysitter for young Bob, the Boyles’ blindingly blonde-haired son. But she may be in league with the supernatural forces that rule the Freudstein house. Bob’s mother, Lucy, seems to sense something is off about Ann. In fact, she knows something is off about the entire house but she soldiers on, the loving if weary spouse of an obsessed academic.

The Boyles’ presence rekindles the ghostly inhabitant of Freudstein House and all manner of jump scares, sudden spooks and not-so-ethereal attacks commence, culminating in an inevitable showdown between man and boogeyman.

The film was released in 1980, which dates it. More substantially – and jarringly – its Italian roots, and its Italian horror sensibility, establish a distance between movie and audience that “House by the Cemetery” may not be able to overcome in the United States. Its case is not helped by the oceans of blood and horrifically graphic violence that, even by today’s standards, will present a challenge to weak-stomached audience members. It could have been worse. According to lore, Fulci was mandated to slay at least some of his darlings to keep the movie at an R rating in the U.S.

More puzzling are the weird lapses in cognition experienced by the characters. For instance, in one scene a woman is brutally (and bloodily) murdered. Her body is dragged across the kitchen and down into the cellar, leaving a blood trail wide as an interstate highway. The next morning Ann, the suspicious au pair, sets about cleaning up the mess (without inquiring as to its cause, which to my mind casts her in league with the devil). Lucy walks into the kitchen, sees Ann down on the floor with her bucket and scrub brush, and asks her what she is doing. Ann says, “I made coffee,” and that answer seems satisfactory to Lucy, who turns and heads toward the stove. Blood trail? What blood trail? The movie is rife with such oversights.

Replete with overly dramatic acting, a musical score that will strike Americans as intrusively silly, and inexplicable gaps in storytelling, “House by the Cemetery” falls more into grindhouse mockery than art house storytelling.

For those reasons I won’t recommend it. I watched out of a sense of duty to Fulci and Sacchetti, but in retrospect, “House by the Cemetery” wasn’t very good.

If you are a horror purist or a collector of oddball cinema, you might enjoy the movie. Otherwise, try something a bit more modern, and a lot more consistent with reality.

“House by the Cemetery” is available on Shudder.

I rate it a D+.

Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.

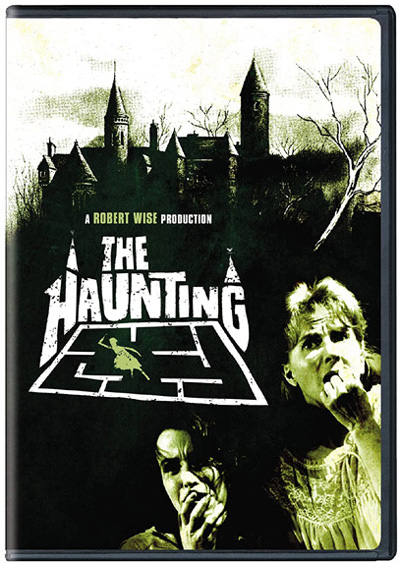

Image courtesy of MGM.

“The Haunting” Starring Julie Harris, Claire Bloom, Richard Johnson, Russ Tamblyn, and Lois Maxwell. Directed by Robert Wise. 1 hour, 52 minutes. Rated G. Shudder.

Del’s take

The opening paragraph of Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House,” upon which “The Haunting” is based, may be the finest paragraph of fiction ever written:

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there, walked alone.”

That paragraph sets the bar for excellence in writing. To match that standard of excellence in another medium, a movie, represents a challenge almost as frightening as the story itself. Robert Wise almost succeeded with “The Haunting,” a scary, atmospheric adaptation of Jackson’s novel released in 1963.

To critique a movie 58 years after the fact seems unfair. Times, people and technology change. By today’s standards “The Haunting” looks silly and shrill. But strip away years of desensitization, computer-generated movie effects and a few evolved cultural standards and “The Haunting” becomes a terrifying excursion into the unknown.

The story is about Eleanor (Julie Harris), in every sense an “old maid” to borrow an expression from that time, who yearns to escape her past. She spent the better part of her adult life caring for her disabled mother and carries a great deal of guilt for not answering her mother’s call for help the night she passed away. When she is invited to participate in a paranormal experiment at Hill House by an anthropologist, Dr. John Markway (Richard Johnson), she takes the family car against her sister’s wishes and drives off into the New England countryside. At Hill House she is joined by a purported psychic, Theodora (Claire Bloom) and young Luke Sanderson (Russ Tamblyn) who is due to inherit the house. The four are besieged by spooky goings-on, including things that go bam bam bam in the night, and ultimately must decide if these are actual events or if they have been primed by the house’s menacing ambiance to imagine them.

Both the book and movie present a question about ambiguity – are there really ghosts at Hill House, as events would suggest, or is poor Eleanor, driven near to madness by a life of caring for her demanding mother while her sister and family go about their lives with purposeful ignorance, simply imagining the voices, loud noises, and sinister airs of that rambling Victorian mansion? One thing is certain: Eleanor is desperate for attention and Hill House gives it to her, and while she seems to recognize the poisonous consequences of that attraction she doesn’t seem to care. She wants to be wanted and she never wants to leave. Hill House has become her lover.

“The Haunting” shows its age with voiceovers to communicate the neurotic internal monologues of Jackson’s protagonist, and quick zooms to suggest a ghostly presence pounding at the bedroom door. A more subtle approach would have more effectively conveyed Nell’s escalating emotional tension (see Jack Clayton’s 1961 production of “The Innocents”). We can also assume a modern audience would not sit still for the slow pacing. Other efforts – Jan de Bont’s 1999 iteration, or the recent Netflix mini-series loosely based on Jackson’s novel – reflect a more modern approach, although one could argue they were not nearly as scary as the Wise production as the novel’s menace is communicated by nuance and implication, not monsters jumping out of closets.

It might not be possible for any filmmaker to successfully capture all the dark corners of “The Haunting of Hill House,” but of the efforts so far, the Wise version most faithfully represents Jackson’s acclaimed book. It is not supremely excellent, like Wise’s 1951 effort “The Day the Earth Stood Still,” but it’s spooky as hell and well worth the nearly two hours of viewing time.

It deserves an A-.

Mladen’s take

A-, Del?

Have you already eaten too much corn candy in anticipation of Halloween?

Has the lingering sugar high distorted your ability to review a movie accurately?

C, Del. “The Haunting” is a C. The film is somewhat entertaining shlock. It’s shlockiness can’t be excused because it was made in 1963.

“Nosferatu” was released in 1922. Still bone chilling. Still eerie.

“Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” 1956. Still ghastly. Still gruesome.

“Psycho” psyched audiences in 1960. Still oedipally demented. Still remembered.

“The Haunting” hovers on just this side of watchable.

“The Haunting” is pinned to an emotionally traumatized person as is “Psycho.” Eleanor, like Norman, can’t help herself. That’s where the similarity between the two films ends.

“Psycho” pulls a stunner at the end. Norman turned victimhood into rage, disorientation, and remorselessness potent enough to rationalize murder. All that “The Haunting” does is keep Eleanor a victim to the disappointing end. First, she is mistreated as a child by her family. Then she’s mistreated as an adult by the diabolical house that also stars in “The Haunting.” Pathetic.

Norman is malevolent. Eleanor mews.

“The Haunting” has some merit. The movie mocks fire-and-brimstone Christianity. It allows for the possibility of the paranormal.

The movie has a couple of solid horror moments, too. Who’s holding Eleanor’s hand during a nightmare? Couldn’t have been Theodora. She was sleeping on the other side of the bedroom. There’s the doorknob and restless door. Both scenes are decent creepiness left to the imagination.

The film’s story is coherent. The first-person exposition pushing “The Haunting” along not too annoying.

The soundtrack would have been better suited for a sci-fi movie of that era rather than a horror flick. Once you’ve heard the simple high key tapping of the piano in “Halloween,” it’s tough to withhold comparison to other horror films no matter the year they were made.

The men in “The Haunting” were dressed as stereotype required. Tweed for anthropology Professor John and a fine jacket with some sort of emblem on the breast pocket for playboy capitalist Luke. Costume design for the ladies was appropriate, as well. Eleanor wore poofy 1950s dresses with flared skirts and sufficiently tight bodices to silhouette perky breasts. Theodora, and I believe this was done to show defiance of social norm and fit her character, wore black, including slacks. She, like Eleanor, was nicely sculpted.

C, Del.

And, this is the finest opening paragraph in fiction:

“Call me Ishmael. Some years ago – never mind how long precisely – having little or no money in my purse, and nothing particular to interest me on shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world.”

The finest opening sentence in any paragraph of any fiction book written is:

“Listen: Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time.”

Mladen Rudman is a former journalist and technical writer. Del Stone Jr. is a former journalist and author.